Simply Steampunk

Writer John Zeaman | Location Morristown, NJ

Bruce, 2017, by Chris Cole of Bend, Oregon, comprises bicycle chain, bicycle cogs, bicycle hubs, bicycle derailleur pulley, bicycle dropouts, motorcycle timing chain, hand-cut and formed steel, salvaged steel, tea strainers, reclaimed door hinges, enamel paint and a hand crank.

The Morris Museum exhibits nostalgia for a long-lost future

For all the light shining on it, the art world still has hidden layers. Poke beneath the surface and you uncover quirky subcultures. Take “steampunk.”

Perhaps you’ve heard the name but don’t know what it means. Steampunk is an antiquarian affection for the early industrial age. In the visual arts, it’s about odd contraptions and mockups that recall the machinery of the Victorian world with an additional twist. These artists don’t just recycle the past. They reimagine its fantasies about the future.

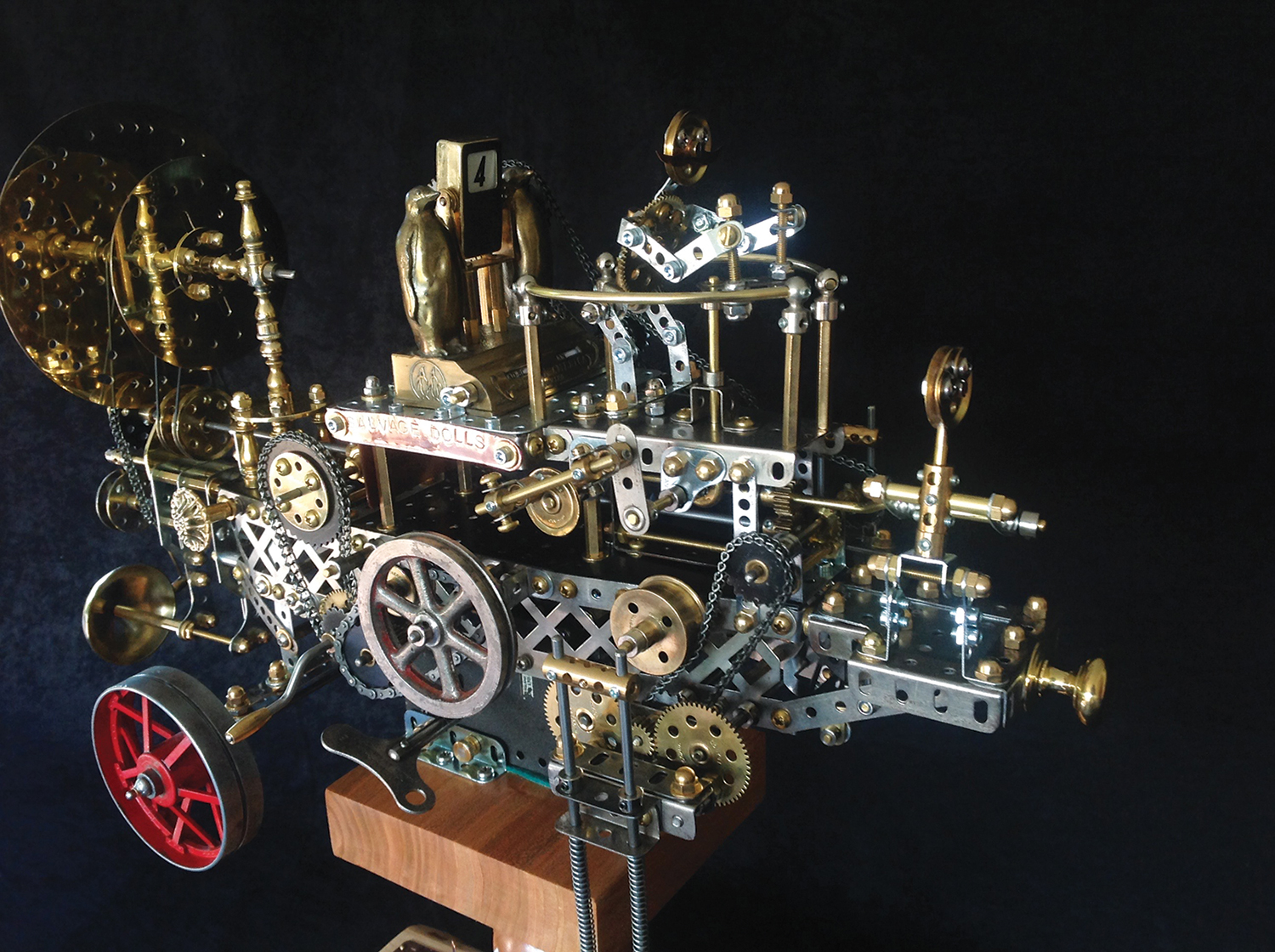

The Flying Machine, 2015, by Ken Draim of Pittsburgh. Mixed media.

Got that? Go back in time, then turn around and look forward through a murky lens. Think 19th-century sci-fi, hot-air balloons, lost cities, time machines and Captain Nemo’s submarine.

It sounds idiosyncratic, but it’s a movement that has attracted artists from around the world. There are exhibits, websites (of course) and even a book or two.

As you may have guessed, the “steam” in steampunk is that of the steam engine, the workhorse of the industrial revolution. Steampunk artists revere the old technology’s brass gauges, riveted steel and mighty pistons.

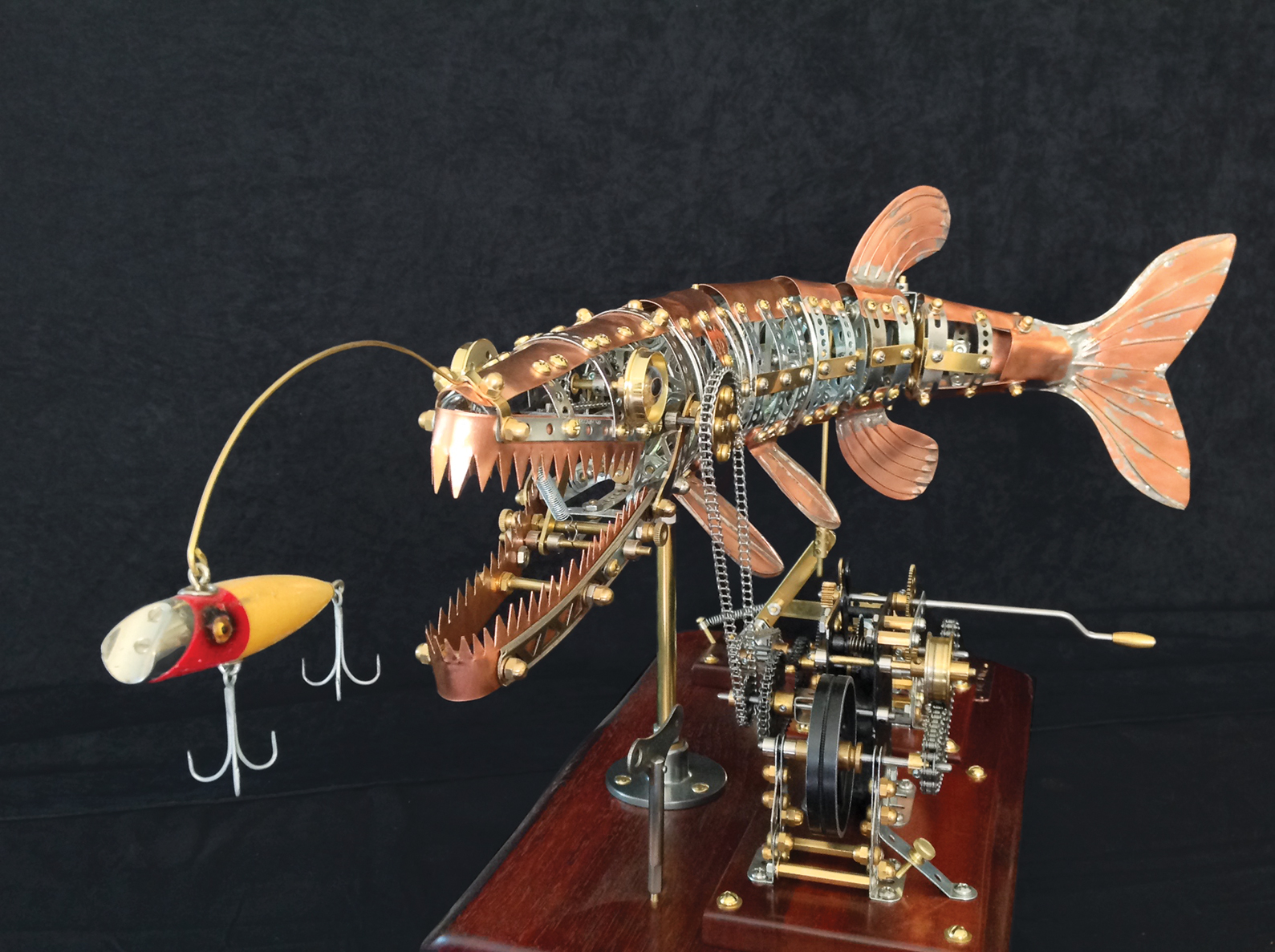

Tink, The Northern Pike, 2018, by David Bowman of Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania, is made of metal and wood.

As for the “punk” part of the name—it comes from the contemporary musical branch of the genre. Steampunk musicians use steam-age props and don costumes in their stage shows. The same is true of some of the visual artists, who appear at openings wearing pilot goggles, pith helmets, derbies and top hats.

My own introduction to steampunk came from the literary side. This was Philip Pullman’s The Golden Compass, a 1995 young adult book that I read with my kids. In its parallel world, machine technology has not evolved beyond single-engine planes, hot-air balloons and primitive electricity. Science and religion overlap. The golden compass of the title is a strange truth-telling device called an “alethiometer.” It would make a perfect subject for some steampunk artist, and probably has.

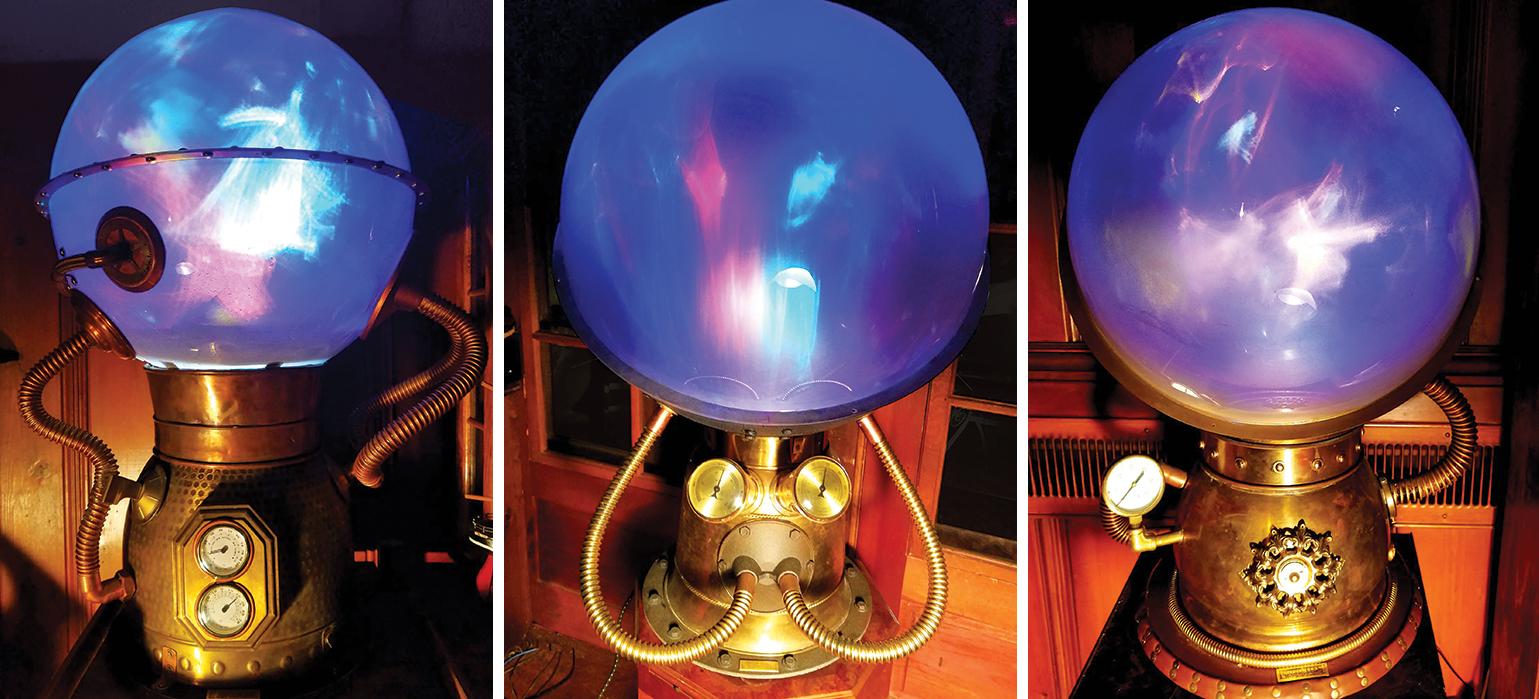

RoboTarium No. 5, 2017, also by Chris Cole, is made of a salvaged voltage gauge, a salvaged bicycle chain, a salvaged driveshaft U-joint, salvaged transmission gear, a motorcycle sprocket and turn signal, steel, a steel spring, a DC electric geared motor, a power inverter and a glass globe.

All this should put you in the mood for Simply Steampunk, an exhibit at the Morris Museum (through August 11). It’s the second in a four-year series titled A Cache of Kinetic Art. Kinetic art is a specialty at the Morris Museum due to its Murtogh D. Guinness Collection of Mechanical Musical Instruments and Automata. Named for the man (of Guinness brewing company fame) who assembled its 750 animated objects, the collection has music boxes and their robotic elaborations from Germany, France and Switzerland, as well as Jersey City, Rahway and Bradley Beach, New Jersey (centers of American music box production in the 19th and early 20th centuries).

Simply Steampunk has 18 mostly movable works by a dozen artists. Push a button and watch things whir, clack and spin. A couple of sound-generating pieces produce robotic bebop music. It’s the kind of show that would warm the hearts of the 18th- and 19th-century designers of the Guinness collection’s music boxes and mechanical figures.

Chris Cole puts machinery under a bell jar to create the mechanical equivalent of a terrarium—what he calls a RoboTarium.

This sculptural piece is by Will Rockwell of West Orange, NJ, titled Lumia Series: Orion Lumia, Hubble Lumia & Messier Lumia, 2018.

A work that cries “punk” is Chris Cole’s Bruce, a piranha-like fish that is all head and nasty-looking jaws. Its metallic ferocity is softened by its sleepy, heavy-lidded eyes. Much of the fun in pieces like this is seeing how materials from one realm (machinery) are adapted to another (biology). The fish’s contours, for example, are elegantly defined by bicycle chain. Somewhere in its anatomy is a tea strainer.

The show has another piscine being, Tink, the Northern Pike. The robotic fish flexes its tail and opens its mouth realistically as it closes in on a fishing lure. The artist, David Bowman, used parts from an Erector Set to construct this and two other pieces, Pterence, the Pteranodon, a flying dinosaur, and Time Machine. The latter employs clock gears and chains to evoke a device that penetrates the fourth dimension. Unlike the human time traveler in H.G. Wells’s novel, this one is apparently robotic, made of the same stuff as the machinery it operates.

Airships are big with steampunk artists. Ken Draim’s The Flying Machine is a detailed model of a zeppelin moored to a rusty docking station. It’s meant to look funky and patchwork, like an old cargo ship.

You read a lot about robots and artificial intelligence nowadays, but Walter Rossi’s headless mannequin The Going belongs to an earlier age. The life-size feminine shape is reminiscent of the robot in Fritz Lang’s silent film masterpiece, Metropolis, but without the sinister character— and minus a head. It’s not clear why she is headless, but she strides ceaselessly forward like a woman on a Nordic Track Ski Machine.

The Going, 2014, by Walter Rossi of New York City, is metal and plastic.

Morristown, New Jersey, artist Kenneth MacBain’s wedding ring has a miniature bear trap around the jewel, a warning about the pitfalls of marriage and its concept as ownership. More steampunky is Will Rockwell’s Lumia Series, a trio of shimmering globes. They are a tribute to a mid-20th century artist named Thomas Wilfred, a pioneer in light art. Wilfred used simple lightbulbs combined with reflective surfaces, color filters and projection screens to create displays that, as Rockwell writes, “suggested the birth of nebula, a cosmic dance.” Rockwell perches his frosted globes on steampunk pedestals—brass with gauges and hoses—to evoke sci-fi crystal balls filled with mysterious undulating lights.

Not all artists fit neatly into the steampunk niche. Matthew Steinke’s wall-size circuit board blinks and bleeps like a computer from a 1950s science fiction movie—more electropunk than steampunk.

Time Machine, 2018, also by David Bowman, is made of metal and wood.

Earlier epochs always seem more golden than our own. It’s worth remembering that many Victorians were horrified by what they saw as the dehumanizing effects of industrialization. They were nostalgic for the Middle Ages when all manufacturing was handcrafted. We, in turn, are nostalgic for their primitive steam-powered machines with their visible moving parts.

Will future generations find charm in our own computer chips, LED screens and plastic housings? Will they mount exhibits titled Simply Silicon?

The Morris Museum is at 6 Normandy Heights Road in Morristown. MorrisMuseum.org.

Columnist John Zeaman is a freelance art critic who writes regularly for The Record and Star Ledger newspapers. His reviews of exhibits in New Jersey have garnered awards from the New Jersey Press Association, the Society of Professional Journalists (New Jersey chapter) and the Manhattan-based Society of Silurians, the nation’s oldest press club. He is the author of Dog Walks Man (Lyons Press, September 2010) about art, landscape and dog walking.