New Jersey Shore Impressionists

Writer John ZeamanJersey shore artists of the early 20th century took their cues from the

French impressionists but added their own twists to the genre.

Say “New Jersey shore” and images of boardwalks, amusement piers and acres of sunbathers come to mind. So it may surprise you to know that not so long ago, small art colonies flourished along this very same coastline. In the late 19th and well into the 20th centuries, the Jersey shore’s beaches, quiet bays, and fishing villages attracted artists from far and wide.

New Jersey’s coast was not the only such place on the Northeast seaboard. Provincetown and Cape Ann in Massachusetts, Cos Cob in Connecticut, and Cape Elizabeth and Monhegan Island in Maine also had colonies. The difference is that those places have retained their artistic reputations. On the Jersey shore, it’s as if all remnants of this culture were wiped out by a tidal wave.

“I grew up in Point Pleasant Beach,” says Lambertville art dealer Roy Pedersen, now in his early 70s. “My town played a role in this history, but I had no idea of it.”

Since then, however, Pedersen has been on a one-man crusade to resurrect the treasures of this lost golden age—the paintings and the stories of the people who made them. “The painters who traveled to the Jersey shore were as talented and as sophisticated a bunch as you’ll find anywhere,” Pedersen says. To make this case, he spent 10 years researching and writing a book, Jersey Shore Impressionists: The Fascination of Sun and Sea 1880–1940. He also co-curated a 2013 exhibit on these artists at the Morven Museum and Garden in Princeton.

Pedersen says artists were drawn to the Jersey coast for two reasons. One is the seashore’s interplay of light and water, enormously important to artists committed to plein air ( outdoor), painting, which was popularized by the French impressionists. The other inspiration was to be found in the people—mostly fishermen and their families—who lived in villages along the shore.

“They saw an authenticity in the lives of these people, and by painting them, sought a similar authenticity in their work,” Pedersen says. This idea had its roots in the French Barbizon School, a movement that sought to convey the spiritual fullness of simple work and life on the land.

The first generation of Jersey shore painters were educated in Europe and arrived in the Manasquan River area around 1880. Artist Will Hicok Low, a student of the French masters Jean-Léon Gérôme and Carolus-Duran, spent summers at Brielle and Point Pleasant Beach. His friend, Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson, visited him there, as did the artist Wyatt Eaton, who had studied with Whistler, Gérôme and Barbizon artist Jean Francois Millet. Also in this circle was Point Pleasant artist Caroline V. Cook Sanborn.

Among the Philadelphia artists who came to the shore was the great realist Thomas Eakins, who spent time at Manasquan and Point Pleasant. Eakins’ student and colleague at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Thomas Pollock Anshutz, went farther south and established himself in Holly Beach, now Wildwood. Anshutz had studied in Paris and, like most of the artists of this era, was influenced by impressionism.

Despite the popularity of the label, however, very few American artists were true impressionists. French artists, such as Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro used a system in which dabs of pure color were perceived as blends in the eyes of the beholder. The method produced canvases that mimicked the shimmer and flicker of real sunlight.

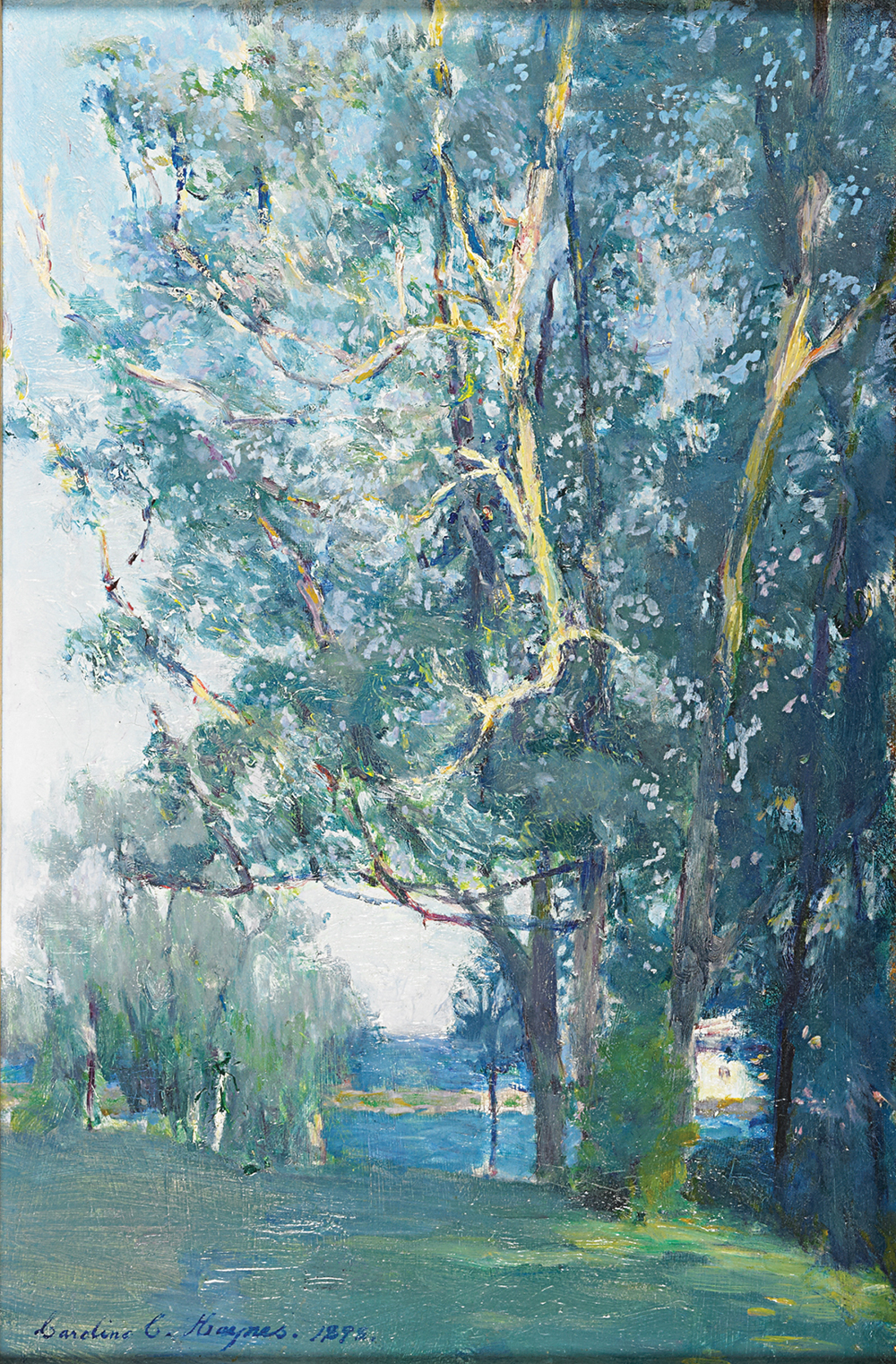

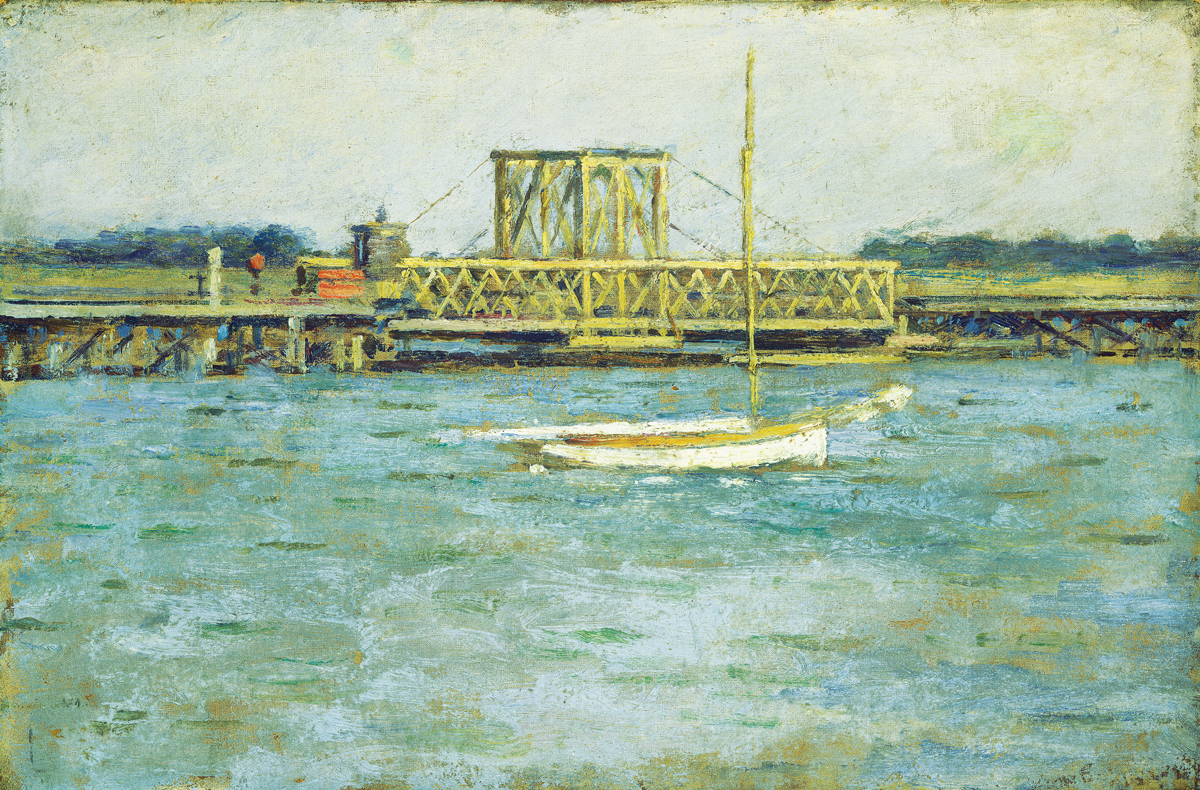

For various reasons, American artists, even those called impressionists today, never went all in with this system. They took what they wanted from it and produced paintings that are quasi-impressionistic, but often dark and moody. Such was the case with Theodore Robinson, Monet’s best friend in America, who sojourned along the Manasquan. Robinson used a scumbling technique (pulling a brush loaded with dry oil paint over a contrasting underpainting), which produced a subtle impressionist vibration, as in his painting Drawbridge, Long Branch R.R. Robinson’s friend, Caroline Coventry Haynes, who also studied in France, painted scenes around Sandy Hook and her family home in Highlands. Like Robinson, she liked overcast skies and — anathema to the French impressionists — a grayish palette.

This moody impressionism had its roots in American tonalism and luminism, a spiritual approach to art in which the desired effect is of dimming light and etherealness. It was mostly incompatible with the French preoccupation with optics and surfaces.

Still, some Americans could summon up a bit of French exuberance, as did Edward Boulton, another student of Eakins, who lived and painted in Point Pleasant for 34 years. His 1894 View of the Manasquan, a slope framed by stunted fir trees, uses dabbing brushstrokes to produce the impressionist vibe.

Other Manasquan regionalists included Albert Grantley Reinhart and Charles H. Freeman. The latter, of Brielle, painted in styles ranging from impressionistic to realist illustration to sweeping panoramas such as his Dunes of 1914.

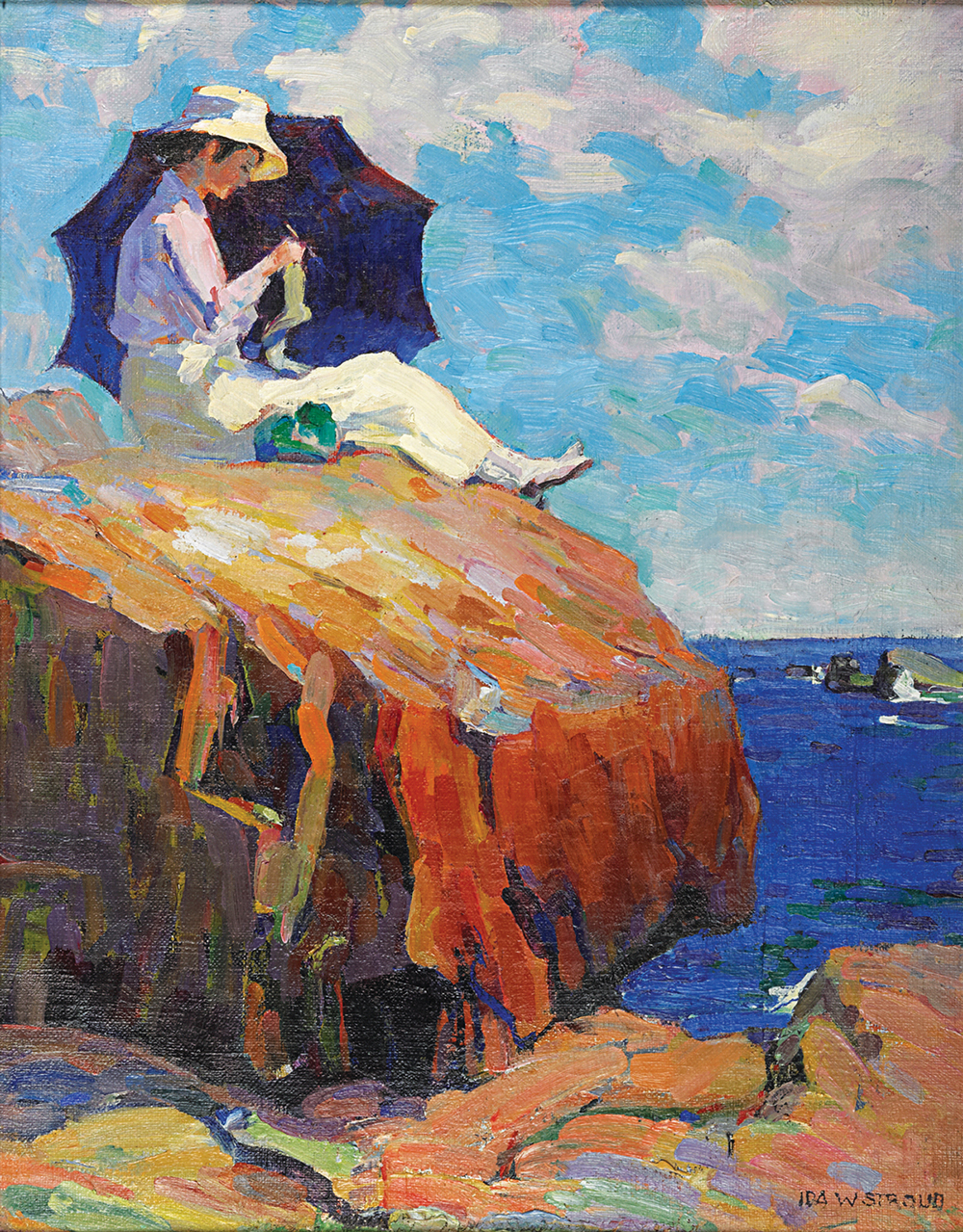

What distinguished the Jersey shore scene from other art colonies was its inclusion of women, Pedersen says. In addition to Haynes and Sanborn, female artists included Elizabeth Grandin, Ida Wells Stroud and her daughter, Clara Stroud, Mildred Miller, Alice Doughten and Marion D. Harris.

“It’s because the shore colonies were not in the orbit of organizations like the Pennsylvania Academy, which kept women out of its exhibits,” Pedersen says. “The Jersey colonies were ungoverned. However, groups like the Bucks County colony fell more in line with the Academy’s authority.”

The Strouds get a long chapter in Pedersen’s book. Ida, who lived from 1869 to 1944, was from New Orleans. She came east and studied at Pratt Institute with Arthur Wesley Dow and William Merritt Chase, then worked and taught in and around the Newark area. She considered herself primarily a teacher and later became involved in the suffrage movement and promoted exhibitions of women’s art.

By this time, modernist styles were supplanting the impressionist and Barbizon models. The 1913 Armory Show in New York City had showcased the paintings of postimpressionists like Cezanne, van Gogh and Gauguin, and the styles that followed, such as fauvism and cubism. Stroud’s painting Clara on the Rocks, with its big simple shapes, shows the modernist influence, as does Paul Gill’s 1929 Beached, with its expressionist brushwork and its push into abstraction.

The second generation of Jersey shore painters worked from about 1915 to 1940. They tended to be schooled in America rather than Europe. Clara Stroud studied at Pratt and the Ringling School in Sarasota, Florida, and later settled in Point Pleasant. In the 1920s, mother and daughter held exhibitions and classes at the Barn Studio in Brick Township.

Spanning both generations was a group of artists who coalesced around the Methodist community of Island Heights. Drawn by its quiet, simple life were James Moore Bryant, Fred Wagner and Frederic Nunn, Carl Buergerniss, John Frederick Peto, Francis I. Bennett and Mildred Miller.

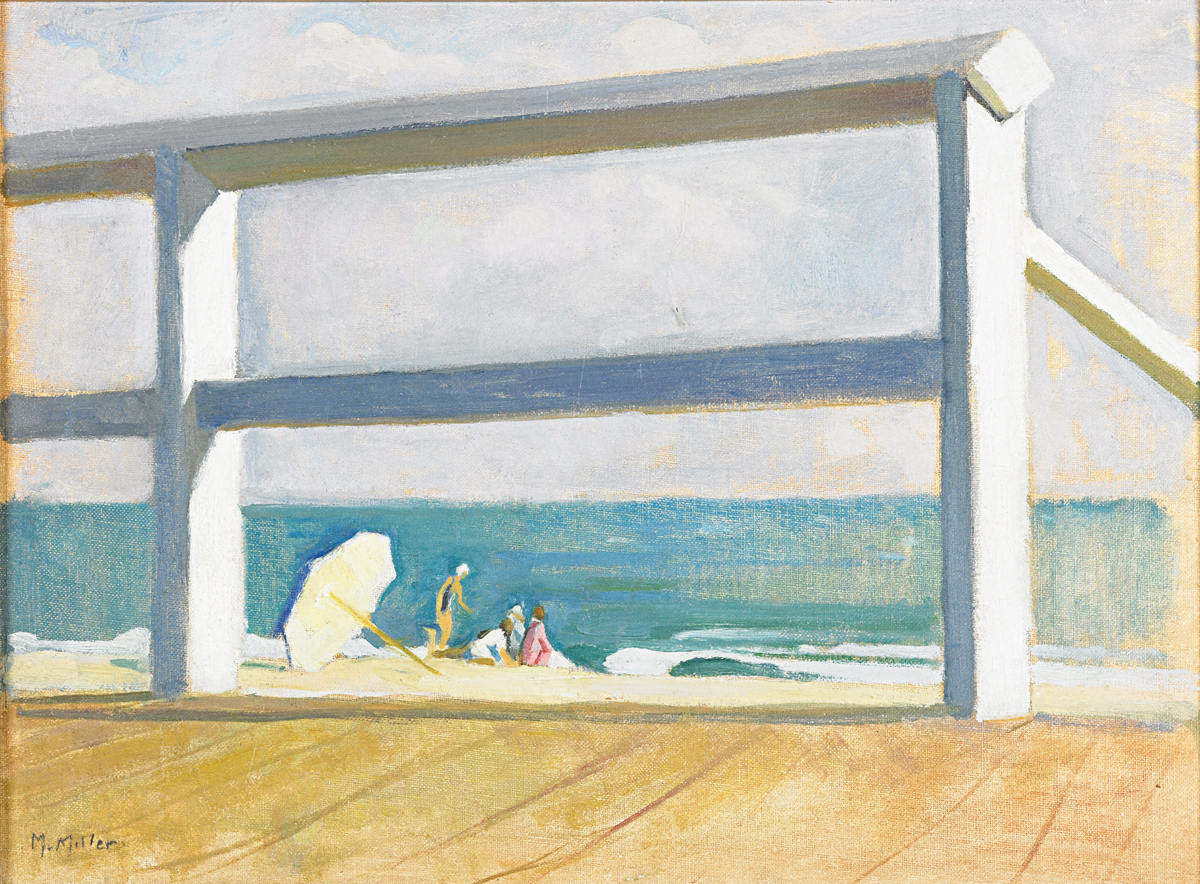

Miller’s 1935 Boardwalk is a charming painting with such clean lines and poster-like simplicity that it could be a work by a pop artist like Alex Katz.

If you’re interested in collecting works of the Jersey shore painters, Pedersen says prices run from $5,000 to $15,000, with the first generation generally commanding the higher prices. Certain popular artists, such as the Strouds, are likewise at the upper end.

Columnist John Zeaman is a freelance art critic who writes regularly for The Record and Star Ledger newspapers. His reviews of exhibits in New Jersey have garnered awards from the New Jersey Press Association, the Society of Professional Journalists (New Jersey chapter) and the Manhattan-based Society of Silurians, the nation’s oldest press club. He is the author of Dog Walks Man (Lyons Press, September 2010) about art, landscape and dog walking.

The Pedersen Gallery is at 17 North Union Street in Lambertville, 609-397-1332, pedersen@pil.net