Mystical Symbolism

Writer John ZeamanOutside the mainstream of spiritual art that was done in the service of conventional religions are works inspired by cults and esoteric philosophies.

Art and religion go hand in hand. At least, it’s been that way for most of art history, from the primitive shamanistic art of Venus fertility figures through medieval Renaissance and Christian art right up to Paul Gauguin with his cosmic questions: “Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?” In fact, today’s art, grounded in pop culture and irony, is the anomaly in this long progression.

Most spiritual art has been produced in the service of mainstream religions, executed by artists who may or may not have been fervent believers. The worldly geniuses of the Italian Renaissance painted Madonnas, angels and crucifixions mostly because that’s where the commissions were. In fact, a perceived lack of genuine religious feeling in the art of Raphael and others led a group of 19th century British painters to found the Pre-Raphaelite movement, which harkened back to the deeper sentiment of the Middle Ages.

Outside the mainstream are the artists inspired by cults and esoteric philosophies. So it was in 1890s Paris, when a charismatic novelist-critic-spiritualist and Rosicrucian named Joséphin Péladan organized a series of exhibits. Rosicrucianism is a mystical cult that sprouted out of Catholicism and whose beliefs include alchemy (turning base metal into gold) and communication with the dead. Such ideas flourished in this period, not unlike the flowering that came out of the 1960s and 1970s that we now inaccurately call “New Age.” Back at the turn of the last century, it was Theosophy and its guru, Madame Blavatsky; the writings of mystic philosopher Rudolph Steiner; Mesmerism; Swedenborgianism; Hinduism; séances and Rosicrucianism.

These exhibits constituted a mostly forgotten chapter in art history that is currently resurrected at the Guggenheim Museum in New York City. The exhibit, “Mystical Symbolism: The Salon de la Rose+Croix in Paris, 1892–1897” (through October 4) is a show of only about 40 works, tucked off the Guggenheim’s main spiral in a gallery of crimson walls and blue velvet furniture. All that’s missing is the incense. Displayed is a shepherdess with a halo, an Eve-Medusa bristling with snakes, a glowing Holy Grail, a line of downcast “Disappointed Souls,” femmes fatales, femmes fragiles, demons, angels and demonic angels. The myth of Orpheus held a particular fascination for this crowd. We see him in dark Hades playing his lyre for Pluto and an even more haunting post-mortem view of his disembodied head floating downstream, now attached to his lyre.

Péladan banned any down-to-earth subjects—no ordinary still lifes, landscapes and portraits. Several portraits of Péladan, himself, made the cut, however. In one, by Jean Deville, he is a monkish figure in white robes, eyes locked on the heavens, his finger pointed up as if to signal a miracle.

Péladan’s salons had no counterpart in America, which is not to say that American artists were not receptive to mysticism. Second-generation Hudson River School painter George Inness was a follower of Swedish scientist-mystic Emmanuel Swedenborg. Toward the end of his life, when he lived in Montclair, Inness’s landscapes became more and more ethereal. This reflected the Swedenborgian belief that the visible world was only a pale reflection of the spiritual one. The Montclair Art Museum’s collection includes a number of these paintings, such as Sunset Glow, in which trees seem to be quivering into insubstantiality.

You can draw a line from Inness to modernists such as Charles Burchfield. The Midwestern artist also looked beyond reality to some otherworldly existence. He tried to make a kind of visual music, pulling moods and rhythms out of skies and fields. Instead of a spiritual essence, his landscapes and houses seem alive. They are animated, even possessed. His work is currently on display at the Montclair Art Museum in an exhibit of watercolors and drawings titled Weather Event. In publicity for the show, curator Gail Stavitsky writes, “Burchfield saw nature as a source of spirituality and was especially awed by the changing of the seasons.”

So what about today? Where are the mystical symbolists of the 21st century? They are even more off the map than the salons of Joséphin Péladan. Despite the dawning of the Age of Aquarius, an overtly mystical contemporary artist is usually pigeonholed into a category such as “visionary” or “outsider artist.”

They tend to band together, sometimes defensively, into groups such as The Society for Art of Imagination (AOI). This group, which has scores of members from all over the world, has been around since 1961. This spring, AOI put on a show in Lower Manhattan titled “Visionary Alchemy.” Members comprise a wildly diverse group, both in style and subject, as well as purpose. Some are pure souls who live for their art. Others come from commercial careers, such as illustration or computer animation.

I’m not sure what Péladan would have thought of their eclectic work, but they meet his criteria in at least one way: their websites feature no ordinary still lifes, landscapes or nonvisionary portraits. So different are the subjects that it’s almost impossible to generalize. In one, churches shaped like hot-air balloons float away from a Venice landscape. In another, Romantic Suicide, a man with the face of a braying donkey leaps from the ledge of a building. A golden serpent weaves through a star-studded cosmos. A giant iguana looms above a cathedral. There are Amazons, ancient kings, wizards, holy men, dragons, skeletons, unicorns, dolphins in space, floating architecture and naked women—some with bird’s wings, some with bird’s heads.

Unlike their counterparts in late 19th-century Paris, however, today’s artists seem unconnected to any particular philosophy or religious belief. Each is on his own, free to explore the vast, unstructured world of imagination, just as an earlier generation of artists explored the world of nature and reality.

Despite their otherworldliness, they are a technically disciplined group. They know how to design, compose and—in an art world that barely teaches draftsmanship anymore—they know how to draw. Not only that, but because almost every work is a complete fantasy, they can pull off an even tougher feat—they can draw from images in their heads.

France Garrido of Weehawkin, New Jersey is secretary of the North American chapter of AOI. She takes inspiration from the art of surrealists such as Salvador Dali and Dorothea Tanning, but without the Freudian slant. Instead, she looks to the art of ancient cultures and primitive peoples. One series focuses on mandalas, those sacred and meditative circles that are often seen in Buddhist art. She is not illustrating any religion or dogma, but looking for universals, forms that can be lifted out and used as a structure in her own work. She wants to go back to the beginning, not just before the Renaissance like the Pre-Raphaelites, but pre-everything—before artist movements and manifestoes.

“I am seeking to touch, deep within the viewer’s spirit, a truth or essence. To awaken/nudge/shift the unconscious,” she writes in her artist statement. “Seduction into another world…world of vision and dream.” She has exhibited all over the state of New Jersey—from the Noyes Museum in Oceanville to the Newark Museum to the Washington Street Gallery in Paterson, as well as in New York City and elsewhere in the world.

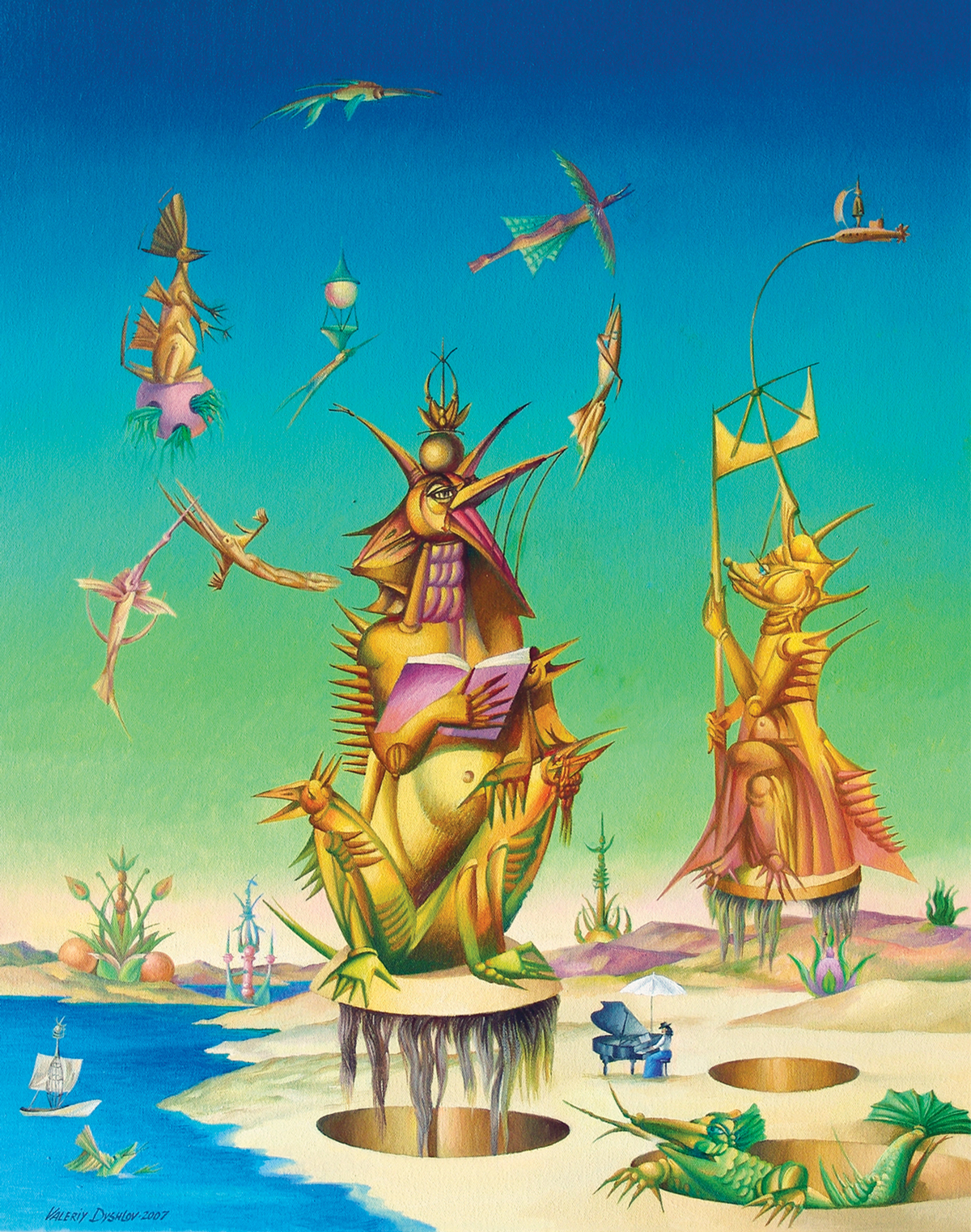

Val Dyshlov was born in Siberia, land of “frosts, white snow and brown bears,” as he puts it. He now lives in Marlboro Township, New Jersey and is a surrealist of the cartoonish and whimsical type. Like Picasso, line is the ruling element in his work. Even in oil paints, he is more graphic than painterly. And, like Picasso, founder of cubism, he is driven to carve and hammer three-dimensionality into faceted forms.

In his own way, he, too, wants to go back to the beginning. Instead of drawing on past cultures, however, he reimagines life, the world, the universe, from the ground up. So it is with his “Fantastic Creatures” series, in which the fauna are cranky-looking bird creatures. They perch in a barren landscape (albeit, equipped with hydraulic-looking platforms that lift them from below), and like creatures from a Beckett play, they squawk out meaningless announcements, warnings, gossip, self-promotions and declarations of war—in other words, they do all the usual human things.

Dyshlov immigrated to the United States from the Ukraine in 1995 and exhibits in various galleries. His work has a strong presence in the Zimmerli Museum at Rutgers in New Brunswick, New Jersey, part of a gift from the collector Norton Dodge, who specialized in Russian underground art.

Anthony Santella is a Teaneck, NJ artist who sculpts in wood and paints quasi-religious pictures and watercolor riffs on fairy tales. His sculpture, Transformations II, is a traditional memento mori—a reminder of death. A woman’s face splits down the middle to reveal the skull inside. As it happens, Santella had a personal relationship with the raw material. The wood came from an 85-year-old red oak that was blown over during Hurricane Sandy, nearly crushing his parents’ house and totaling two cars. He recalls being less traumatized by the close call than the loss of a tree to which he had always felt close as a child.

His oil paintings are treatments of Biblical stories with a contemporary twist. Like Caravaggio, he seeks to make old stories feel relevant with modern-day trappings and more than a little funk and edginess. His Eve, painted on a hand-carved altarpiece triptych, is a far cry from traditional treatments. The apple has already been bitten, the Garden of Eden is gone and Eve inhabits the world of human pain and suffering. She stands in front of the graffiti-marred brick wall of a squalid tenement. There is no sign of an angry God, but Eve, herself, looks sufficiently malevolent and dangerous to convey the drama of the loss of paradise.

For all the deviation from traditional imagery, Santella differs from most imaginative artists in giving his work a cultural context. Most see the dream world as their destination. Viewers are to be brought to the threshold and set free, not given a script or a lesson.

Perhaps it’s just a matter of taste. But freedom of this type can lack the satisfying click that comes when a visual composition fits the slot of a familiar story or myth — the man playing the lyre in a spooky cave, the animals being led onto a great ship or the body being brought down from a cross. Whether the picture-story relationship is closed or open-ended, however, it’s good to know there are artists still grappling with those eternal questions.

Columnist John Zeaman is a freelance art critic who writes regularly for The Record and Star Ledger newspapers. His reviews of exhibits in New Jersey have garnered awards from the New Jersey Press Association, the Society of Professional Journalists (New Jersey chapter) and the Manhattan-based Society of Silurians, the nation’s oldest press club. He is the author of Dog Walks Man (Lyons Press, September 2010) about art, landscape and dog walking.