Michael Graves – An American Legacy

Writer Janet Purcell | Photographer Peter Rymwid Editor’s Note: We were honored when world-renowned architect and product designer Michael Graves agreed to allow us to photograph and write about his Princeton, NJ, home. And we were saddened to hear of his passing in March 2015 shortly after we visited with him. With the blessing of his staff, we presented the story as planned. We wish his staff well as they continue his company, Michael Graves Architecture & Design, and turn his beloved home into a non-profit foundation and study center to inspire generations to come. This article appeared in our 15th Anniversary issue, August/September 2015.

Editor’s Note: We were honored when world-renowned architect and product designer Michael Graves agreed to allow us to photograph and write about his Princeton, NJ, home. And we were saddened to hear of his passing in March 2015 shortly after we visited with him. With the blessing of his staff, we presented the story as planned. We wish his staff well as they continue his company, Michael Graves Architecture & Design, and turn his beloved home into a non-profit foundation and study center to inspire generations to come. This article appeared in our 15th Anniversary issue, August/September 2015.

“It had good bones.” Michael Graves was matter of fact as he remembered his first reaction to the rundown warehouse he discovered while taking a leisurely walk in Princeton, New Jersey. “Its construction was what I remembered from my time in Italy, the barns in Tuscany especially.”

A recipient of the coveted Rome Prize for the highest standard of excellence in the arts and humanities, Graves spent 1960-1962 at the American Academy in Rome drawing the region’s barns and buildings. It was to be a period that strongly influenced not only his career but his personal lifestyle as well.

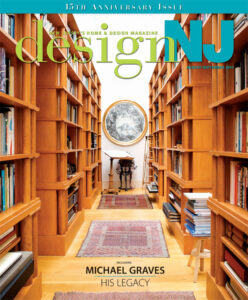

A wisteria-entwined loggia extends the library’s quiet space to the outdoors, where a line of pleached trees and a pair of circa 1880 Mediterranean terra-cotta oil jars stand guard. A flea market-purchased table and bistro chairs offer a comfortable place to enjoy this oasis.

The old warehouse he discovered on his walk that day was built in 1927. Italian masons who came for construction projects at Princeton University built the warehouse strong and divided its two stories into dozens of windowless storage spaces with walls and ceilings made of hollow clay tiles. None of its 44 rooms measured more than 10 feet long.

“The place was a mess,” Graves said. “Water was leaking everywhere, and the floors were filthy. There was no plumbing or heat and the wiring was all bad, but I didn’t want it to be torn down. I wanted to save it.” He purchased the derelict warehouse in 1974 for $30,000.

“I hadn’t been teaching at the university very long and wasn’t able financially to do much renovation,” he recalled. “I had a studio at the university, but the department moved. So I came and lived here for 10 years like one of my students with just a piece of plywood on saw horses and a sink and stacks of dishes and glasses.”

Left: Michael Graves in his library, with most pertinent titles at hand level. He would select a book and then retreat for reading in the adjoining living room. Right: Above a pair of matched 19th century Biedermeier chests flanking the library doors are two Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot copies that Michael Graves painted. A pair of tripod reproductions of first century brassieries that can be used as small coffee tables and a pair of Graves-designed lounge chairs complete the room’s balanced layout. Flowers in a blue glass vase with bronze armature, which Graves designed, sit on a 19th century Biedermeier table and add a graceful note to the room’s symmetry.

It took more than 30 years and “hundreds of thousands of dollars,” with Graves doing much of the work himself, but he turned the old building into a home that exudes elegance as well as a warm, welcoming ambience, much like the man he was.

Everyday Enjoyment

Through the years, Michael Graves merged his architectural expertise and artistic sensibilities with his credo that “the look and feel of everyday things can enhance life.” He applied this concept to the renovation of his L-shaped home, which is like a Mediterranean oasis in an American college town.

World-known for his prominent public building commissions and the exuberant Disney World Hotels in Florida, Graves was even chosen to design the unique scaffolding that surrounded the Washington Monument during its recent renovation. The Resorts World Sentosa in Singapore is among dozens of his other impressive achievements. In 1999 he was awarded the National Medal of Arts. In 2001 he received the American Institute of Architects’ Gold Medal and in 2010 the AIA Topaz Medal, among many other honors. He also became widely known in the commercial market for designing more than 2,000 products for clients such as Kimberly-Clark, Stryker Medical, Alessi, JCPenney, Target and Disney. He also was an accomplished artist with gallery representation at Studio Vendome in Manhattan’s SoHo district.

Graves was a generous man, often lending his name, expertise and energy to help others. One of the organizations he was most passionate about is the Madonna Rehabilitation Hospital in Omaha, Nebraska. He believed in the hospital’s mission and vision in rebuilding lives using world-class technology, translational research and family-like culture. Memorial gifts in his name are being used to help build the rehabilitation hospital, which he designed, and to honor him through a permanent naming opportunity. More information about the design project can be found at madonna.org.

At Home, a New Beginning

When Graves was struck in 2003 with a spinal infection that left him with lower-body paralysis, he designed renovations to the home that made living with his disability more comfortable. “I’ve designed one-story Wounded Warriors homes so they wouldn’t need elevators,” Graves said. But rather than sell and move to a one-story home, “I loved this place, so I put in an elevator.”

He bumped out an outside wall to allow space for the elevator, and he completely redesigned his upstairs bathroom, taking space from a former closet and installing drains for a roll-in shower.

His original renovation of the warehouse included a skylight that allowed light to filter down into the first-floor foyer through a circular, balustraded opening in the second-story floor. To allow easy wheelchair passage, the balustrade was removed and solid glass was installed in the opening.

“You just have to use common sense,” he said.

That attitude guided him through all the renovations to the point where he no longer considered his home a warehouse. “I love it with a kind of compassion where all the rooms are set up in such a way that it’s a work of art,” he said. “It took some imagination to convert it, but I wanted to save it and, as I did, I came to love it.”

Michael Graves always encouraged his students to be lifelong learners after school. His life at the warehouse was just a prologue for his dream that it will endure as a non-profit foundation and study center to inspire generations to come. His estate is now working to make this dream into a reality.