Making Their Marks

Writer John Zeaman

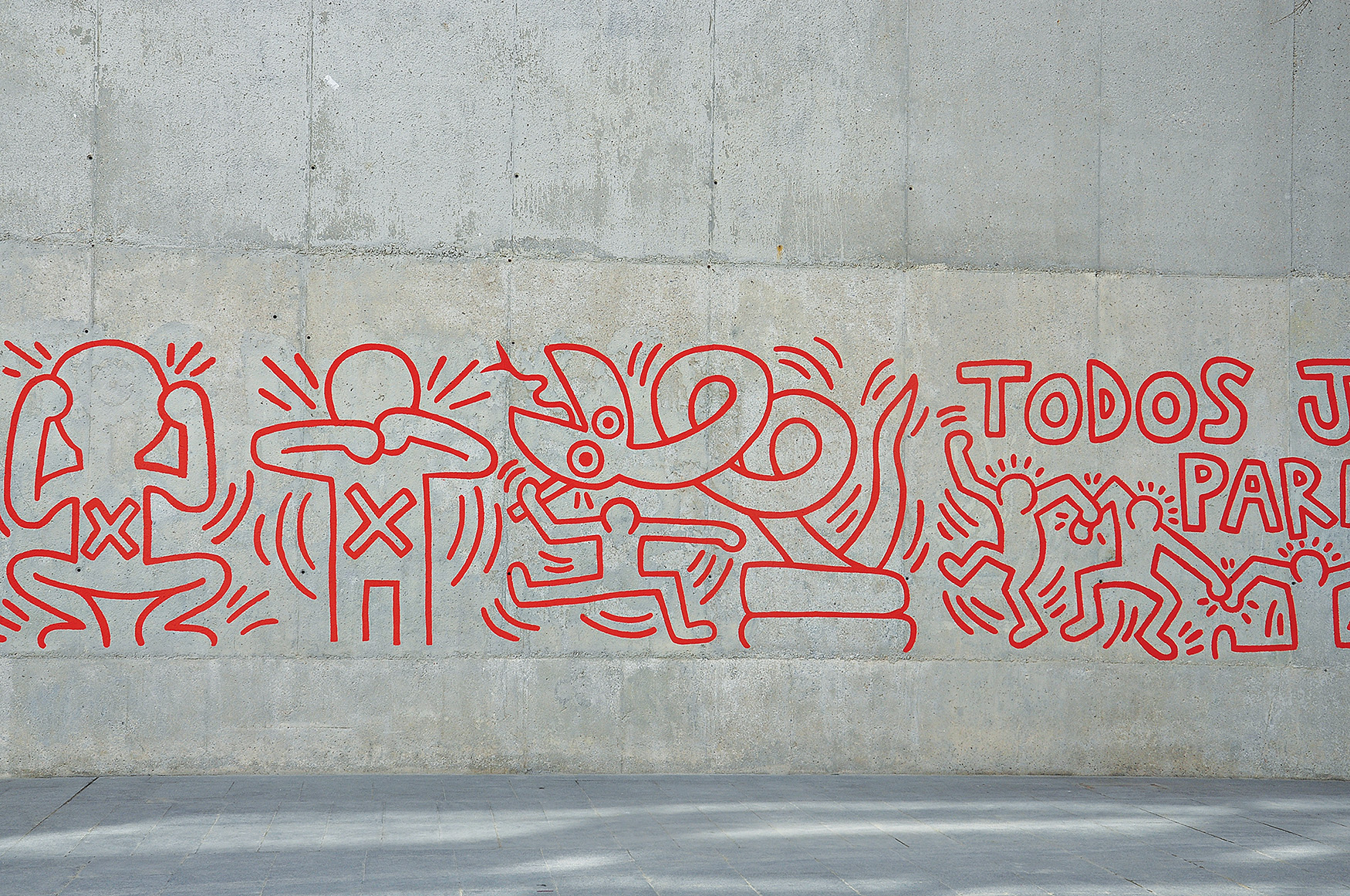

Graffiti artist Keith Haring at work in the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in 1986 and a mural by Haring at the Barcelona Museum of Contemporary Art in Spain. Unlike many New York City subway graffitists, who spray-painted the trains themselves, Haring worked on the subway platform. He had to work quickly, trying to finish before the next train pulled in, giving his art its distinctive shorthand appeal. Image courtesy of the Netherlands National Archive.

Young artists drawn to handmade notations

Art has lots of buzzwords. Here’s a new one, at least to me: “mark making.”

What does it mean?

In the loosest sense, it’s simply the act of putting marks on a surface. But in art, that definition takes in too much—from prehistoric cave drawings to old master paintings to scribbles by toddlers—so it’s not very informative.

A friend who teaches at an art school in New York City says mark making is the starting point in courses on two-dimensional design: “We begin with a basic vocabulary. A brush does this. A pen does that. Then we try to show how these elements can be used in drawing and compositions.”

What surprises my friend is that many students take a shine to mark making as if it were an end rather than a means, a style rather than a basic building block.

A more salient definition of mark making might be a kind of art in which the individual strokes become as significant as the image.

I googled “mark making in art” and was surprised at how much there is on the internet: “How Does Mark Making Affect Your Paintings?” “Mark Making Ideas,” “Mark Making Tools,” “Mark Making Textures,” “Mark Making Exam Help,” “148 Best Expressive Mark Making Images in 2019.” Grids illustrate squiggles, zig-zags, dots-and-dashes, cross-hatching, parallel arcs. There are YouTube videos, books and discussion threads.

Ink Painting

Despite its currency, mark making isn’t something new. In art history, the earliest self-conscious mark-making occurs in Asian art. Chinese ink painting began around 600 AD. It spread to Japan, where it is called Sumi-e. In these traditions, calligraphy and painting are close cousins.

The idea is to create an image with as little ink as possible and to capture the essence of a thing rather than to describe it in detail.

“Haboku-Sansui” by Japanese artist Sessü Tōyō (1420-1506) is a vertical scroll with a landscape painted in the “splashed ink” technique. The near-abstract composition includes suggestions of mountains, trees, water, a boat and rooftops. Image courtesy of the Tokyo National Museum.

Consider “Haboku-Sansui” (or “Splashed Ink Landscape”) by the great medieval Japanese artist Sesshü Tōyō. Within its near-abstract composition are mountains, trees, water, a boat with rowers and rooftops. Parts of the image are practically illegible, but Sesshü sought to convey the feeling of the scene with deft and subtle brushstrokes. It is impossible to appreciate this picture without admiring the execution, the marks that make the image.

It took a long time before anything similar evolved in the Western tradition. Painters in medieval or Renaissance Europe took pains to conceal their brushstrokes. Their goal was a smooth, mirror-like surface that preserved the illusion of a window on a world.

This changed in the more emotional Baroque period. Old master painters such as Peter Paul Rubens and Rembrandt were virtuosos who sometimes worked in what is called a bravura style. Bravura painting is like a thrilling performance. Artists show off their skills with visible brushstrokes and unpolished surfaces—as if to say, “see how quickly and effortlessly I can do this.”

In the Romantic period, painters such as Francisco Goya and Eugène Delacroix weren’t so much showing off as using gestural marks to convey passion. Their opposite numbers were the classicists, such as Jacques-Louis David or J.A.D. Ingres, who suppressed brushstrokes in favor of clean lines, crisp edges and calm horizons.

The impressionists certainly made marks, but it had nothing to do with gesture or bravura painting. Their technique was essentially scientific. They had discovered a perceptual principle: that dabs of pure color in proximity would blend together in the viewers’ eyes and brains. The result was a visual sparkle akin to the experience of outdoor light.

The exception among the impressionists was Claude Monet. Early in his career, he did adhere to the scientific model. He was one of the most methodical of the impressionists, recording the way light changed over the course of a day on such subjects as a haystack or a cathedral façade. Later, he became more of a mark maker. Some say this was due to blurred vision from cataracts. Whatever the reason, his late water lily paintings achieved an elegant abbreviated style, like Asian ink painting.

His contemporary, portraitist John Singer Sargent, was a bravura painter with few equals. He swaggered across the canvas with a loaded brush, deftly rendering the billows in a silk blouse or the folds in a satin dress with strokes that bring excitement to what might otherwise be perfunctory passages.

Expressionism

That brings us to the quintessential mark maker in the Western tradition: Vincent Van Gogh. He took the little scientific dabs of the impressionists and turned them into expressive dashes that seem to feel their way across the surfaces of things. You see it in “Country Road in Provence by Night” with its cypress trees shooting up like flames. Or in “Starry Night,” where the dashes become swirling celestial halos. Van Gogh’s insistent, energetic brushstrokes became a hallmark of expressionist art.

Vincent Van Gogh took the little scientific dabs of the impressionists and turned them into expressive dashes that seem to feel their way across the surfaces of things. An example are these cypress trees shooting up like flames in his “Country Road in Provence by Night.” Image courtesy of the Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands.

Some 70 years later another generation of artists made the brushstroke even more important. These were the abstract expressionists— painters such as Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline and Jackson Pollock. Critics talked about the miles-per-hour speed of their brushes. Some retained a semblance of imagery—a mouth here, an arm there. Pollock gradually weaned himself from imagery until one day he threw it all out and strokes became the painting. Pollock preferred to work horizontally, tacking his canvas to the floor so he could pour, drip and splatter the paint. He claimed to have no plan when he worked, relying entirely on intuition.

This installation at the Museum of Modern Art shows two Jackson Pollock paintings: “The She-Wolf” (1943) at the left and “Gothic” (1944). For Pollock, an abstract expressionist, strokes became the painting. He preferred to work horizontally by pouring, dripping and splattering paint onto a canvas tacked to the floor.

Graffiti Artists

After the abstract expressionists came the pop artists. Their art was less about marks than sly attitude, a campy take on commercial culture. It severed all connection with the art of the past and rooted itself in advertising, comics and celebrities. Roy Lichtenstein poked fun at the super seriousness of the abstract expressionists with a cartoonish image of a paint-laden brush. So much for mark making!

One of the pop crowd, however, drifted into a style that seemed obsessed with mark making. This was Cy Twombly. His art looks like scribbling or the penmanship exercises of an old grammar school education. Think of an illustrator, say, who wants to render a handwritten note without making anything legible. You’re just supposed to read it as handwritten note. Twombly’s art alludes to a lot of calligraphic marks—signatures, scrawled messages, Roman graffiti (he lived in Italy).

If Twombly’s art was a cerebral take on graffiti, Keith Haring’s art was the real thing. The young Haring came to New York in 1980 at the height of the subway graffiti movement. Unlike the subway graffitists, who spray-painted the trains themselves, Haring worked on the subway platform. He used white chalk to draw on the black backing paper in empty advertising frames. He soon developed a popular cast of cartoonish characters: radiant babies, flying saucers, barking dogs and cult worshippers. The speed with which he drew, trying to finish before the next train pulled in, gave his art its distinctive shorthand appeal.

Not all graffiti artists are mark makers. The street artist Banksy is an example. Like graffiti artists, his work appears overnight on public walls, but it’s made with stencils, as shown in this example, called “Girl Seized by an ATM.” You can’t use stencils and be considered a mark maker. Photo by Bengt Oberger.

The subway graffiti trend continued with Jean-Michel Basquiat, who began his career underground writing hip aphorisms above the tag of SAMO. Later, as a protégé of Andy Warhol, he made paintings that are like giant angry doodles, busy and diagrammatic. They’re also scary and chaotic, with screaming faces and skulls, robot heads, black blotched-out passages and slogans, such as “power & money.” They look untrained and spontaneous, like an impromptu mural on a ghetto wall.

Not all graffiti artists are mark makers. The street artist Banksy is an example. His work appears overnight on public walls, but it’s made with stencils, a mechanical means of image duplication. You can’t use stencils and be considered a mark maker.

So mark making has been with us, in various forms, for hundreds of years.

My art professor friend isn’t happy, however, with the contemporary mark-making aspirations of his students. He feels it gets in the way of their development. “It’s the enemy of drawing,” he says.

How is it that mark making has become popular with a generation that has grown up without training in penmanship and that rarely communicates through handwriting?

It seems a paradox, but perhaps there’s a logic to it. For those raised on texting, memes, emojis, selfies and videos, the handmade mark is a novelty, something ancient and discarded and now, presumably, reclaimed as art.

A Mystery Solved

The identity of a French artist revealed

In our August/September 2018 issue, we told of a Bergen County woman’s effort to unravel the mystery of a printmaker known only as “Hubert.” Coral Petretti had been obsessed with this artist since finding a hand-colored etching signed “Hubert” behind a broken frame in the mid-1980s. Since then, she had talked to countless experts, combed Parisian flea-market stalls, collected some 200 of his prints and kept a blog called “Chasing Hubert.”

In our August/September 2018 issue, we told of a Bergen County woman’s effort to unravel the mystery of a printmaker known only as “Hubert.” Coral Petretti had been obsessed with this artist since finding a hand-colored etching signed “Hubert” behind a broken frame in the mid-1980s. Since then, she had talked to countless experts, combed Parisian flea-market stalls, collected some 200 of his prints and kept a blog called “Chasing Hubert.”

In all that time, she continued to believe in Hubert’s aesthetic merits, even when experts labeled him a likely anonymous “souvenir artist.” Then, at about the time the Design NJ column appeared, she heard from a French scholar who had come across a print of a Parisian scene signed “Leon Salles-Hubert.” Petretti recognized the hand of her beloved Hubert. Other confirmations followed.

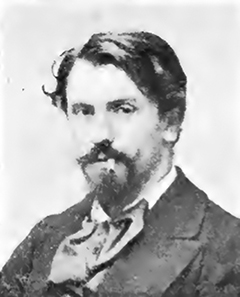

Salles apparently worked under several pen names, including Hubert, which was the maiden name of his mother. The painter-etcher lived from 1868 to 1952. In the late 1890s, he won awards at the prestigious annual Salon of French Artists and a medal at the Paris Exposition in 1900. His Wikipedia entry even has a blurry photo of him. He looks very dashing, sporting a cravat, with a cigarette dangling from the corner of his mouth.

So Petretti’s faith has been vindicated. But the resolution of the mystery has not dampened her interest.

“It’s sparked it even more,” she says. She already owns several pieces signed by Salles and sees little difference in the quality of the work done under the supposedly commercial pseudonym. “Two of the Salles prints look identical to ones signed by Hubert,” she says.

Read the original feature here.

Columnist John Zeaman is a freelance art critic who writes regularly for The Record and Star Ledger newspapers. His reviews of exhibits in New Jersey have garnered awards from the New Jersey Press Association, the Society of Professional Journalists (New Jersey chapter) and the Manhattan-based Society of Silurians, the nation’s oldest press club. He is the author of Dog Walks Man (Lyons Press, September 2010) about art, landscape, and dog walking.