Life Like

Writer John Zeaman | Photographer Erik Christian Photography

Carolyn D. Palmer in her studio with her bronze sculptures of Popes Francis, Benedict XVI, John Paul II and Paul VI.

Sculptor Carolyn D. Palmer creates masterpieces in her Saddle River, New Jersey studio

A bronze statue is one of those honors bestowed on the immortals or, at the very least, those with a contemporary purchase on it. The merely wealthy settle for oil portraits. It usually takes a government agency, a presidential library, a church or some such group to commission a life-size bronze.

That’s not to say that everything cast in bronze must be as grave and heroic as a general riding on horseback. A statue of early sitcom bus driver Ralph Cramden (Jackie Gleason in “The Honeymooners”) stands outside the Port Authority bus terminal in New York City. There’s even one of the goofy and portly Lou Costello in his hometown of Paterson, NJ.

But we’ve yet to see private individuals putting bronze statues of themselves on the front lawn.

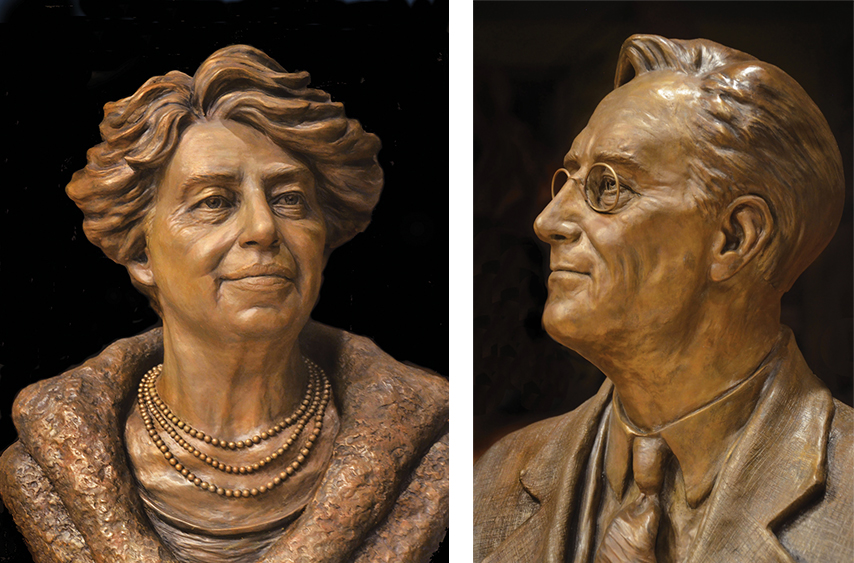

Eleanor and President Franklin D. Roosevelt in bronze, commissioned for the lobby of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum in Hyde Park, New York.

Sculptor Carolyn D. Palmer’s client list fits this zeitgeist. Standing sentinel outside the front door of her Saddle River, NJ home is Thomas Jefferson. Inside, you’ll find a quartet of popes, the Wright Brothers, Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt, Mother Teresa, Mario Cuomo, Bill Clinton and, perhaps fittingly, a still-unfinished Hillary.

But her most famous commission, which she showcases in photos and a clay study at the front of her studio, is her bigger-than-life bronze of Lucille Ball. It was unveiled in the summer of 2016 in Lucy’s tiny hometown of Celoron, NY. Palmer portrayed the 1950s TV comedienne sashaying in a polka-dot dress, one hand on her hip, the other lifting her hem a bit in a flourish. The sculpture has style and verve. It deserved the widespread praise it received, but a lot of the media attention had to do with its infamous predecessor, “Scary Lucy.”

That’s the nickname given to a clumsy, grimacing statue that was erected in Lucille Ball Memorial Park in 2009. The sculptor, Dave Poulin, drew inspiration from a specific “I Love Lucy” episode in which she pitches a made-up remedy called Vitameatavegamin. The sculpture aims for the moment when Lucy tastes a spoonful of the vile stuff. Lucy was known for her clownish faces, so the idea had merit. But Poulin failed in the portrait artist’s first obligation: to render a credible likeness. The statue existed in homely obscurity until 2015, when it became the object of internet ridicule. Some posts twinned it with a picture of actor Steve Buscemi; others, the snake in “Beetlejuice.”

Lucille Ball statue in her hometown of Celoron, New York.

That was too much for the folks of Celoron (population 1,250). They started a movement for a new statue, with donors putting up a reported $250,000. Palmer, who had turned from portrait painting to sculpture only about 15 years earlier, beat out some 65 other applicants. She worked on the piece for about nine months, during which she watched countless episodes of “I Love Lucy” and hired models who matched Ball’s 5-foot-7-inch stature. “New Lucy,” as she dubbed it, was unveiled on Ball’s 105th birthday.

A close-up showing the incredible detail.

Given the criticisms of the first Lucy, it’s not surprising that Palmer steered clear of clownish and went for the super-feminine. “I wanted her to look peacocky and confident,” Palmer says. “She was a beautiful and fashionable lady.”

In a postscript to the Lucy story, Celoron elected to keep the old sculpture in the park. The internet infamy of “Scary Lucy” had made her a tourist attraction too. She now stands some 75 feet from “New Lucy” and most visitors snap a picture of both.

Palmer is originally from Orange County, New York, and moved to Saddle River, New Jersey just a few years ago. Her elegant house sits on a spacious lot in a Bergen County, NJ neighborhood of mansions and historic manors known for its rich and famous residents (Richard Nixon made it his home in the last decade of his life).

Given the demands of life-size sculpture, her studio is surprisingly modest in size—nothing like the barn-like ateliers of Auguste Rodin or other past masters of her genre. It’s just a room within her house and as crowded with figures as a Chinese emperor’s tomb. Tall windows overlooking the sloping wooded land behind the house preserve an airy feel.

The artist releasing a mold in the making of a sculpture.

There are works in progress here, but many of the pieces are the clay originals of finished commissions. It’s a reminder that one of the plusses of being a sculptor instead of a painter is that you often get to sell your work and keep it too.

The ingenious technique that transforms a malleable lump of clay into a nearly indestructible sculpture has remained essentially unchanged for the past 6,000 years. It’s called the “lost-wax” method. It involves a sequence of molds and pours using different materials. Eventually you get a fire-resistant mold with an internal layer of wax that conforms to the shape of the original sculpture. When heat is applied the wax melts out (is “lost”). The now-empty channels of the mold are filled with molten bronze. Steam and heat escape through vents and pipes. When everything cools, the ceramic mold is broken open and the pipes snapped off. The result is hollow metal sculpture.

Front and center in Palmer’s studio are the red clay originals of her most recent project: busts of four popes who visited New York City’s St. Patrick’s Cathedral: Paul VI, John Paul II, Benedict XVI and Francis. The finished bronzes have been installed on marble shelves in the left and right vestibules of the famous cathedral.

Cardinal Joseph Tobin, Archbishop of Newark, New Jersey looks into the eyes of the Pope John Paul II sculpture in Palmer’s studio. He was there to bless the sculptures before they were taken to New York City for placement in St. Patrick’s Cathedral.

Palmer relishes the tactile aspect of sculpture. As she talks about her pieces, she runs her hands over their surfaces. She pops the crucifix off Pope Paul’s chest to demonstrate how some details of sculptures are cast separately. She fiddles with a practice bust of Lucy’s head to show how she did the eyes on the finished one (that full-size original unfortunately broke apart when the mold was opened).

“Lucy wore false eyelashes,” she explains, “so I had to figure out how to do that.” She produces a sliver of clay, presses it to the upper eyelid of the sculpture, and then, taking a tool with a wire loop on the end, begins articulating the eyelashes. She’s like a chef demonstrating her pie-crust technique on a cooking show.

The polka dots on Lucy’s dress? She produces the top from a nail polish bottle and begins stamping them out of a sheet of clay, cookie-cutter style. “It was summer when I initially did them and they were too floppy to hold their shape,” she explains. “So I put them in the freezer to firm them up.”

Bronze sculpture need not be completely monochromatic. Lucy was famously a redhead, and Palmer imparted a rust color to the metal of her hair with a chemical treatment.

When there’s a demand, Palmer reproduces busts in shelf and desktop sizes. A popular one with hospitals and medical schools is that of Sir William Osler, a Canadian physician who helped found Johns Hopkins Hospital and created the first physician residency program.

Another shelf has a crop of “little Marios”—Cuomo, that is, the former governor of New York, whose smiling, life-size bust was commissioned by an Italian-American association.

Suppose, I ask Palmer, I wanted a life-size bust of myself. What would that cost? Artists don’t like talking money. Many have dealers to do that for them. But Palmer thinks it over. “Each commission is unique,” she says. “I put in many long, passionate hours creating each sculpture. Fortunately my work is now appraised in the six figures.”

That’s not a bad price for a purchase on immortality.

Of course, first you must lead an exemplary life.

Columnist John Zeaman is a freelance art critic who writes regularly for The Record and Star Ledger newspapers. His reviews of exhibits in New Jersey have garnered awards from the New Jersey Press Association, the Society of Professional Journalists (New Jersey chapter) and the Manhattan-based Society of Silurians, the nation’s oldest press club. He is the author of Dog Walks Man (Lyons Press, September 2010) about art, landscape and dog walking.