Healing Power

Writer John ZeamanA cancer treatment center uses art to aid recovery.

The idea that art can have a beneficial effect on health is not new. Authorities on the subject frequently quote Florence Nightingale, the founder of modern nursing, who long ago wrote about the therapeutic power of “beautiful objects.”

“Little as we know about the way in which we are affected by form, by color and light,” she wrote in 1860, “we do know this—that they have an actual physical effect.”

It’s striking how prescient Nightingale was. Just as striking, however, is how long it took for the idea to gain traction. For most of the 20th century, the technological advances of medical science overshadowed the human factor. Hospitals had state-of-the-art equipment, but they tended to be cold, impersonal places.

That has begun to change. Doctors recognize that the human immune system can get a boost from elevated emotional states and that those states can be affected by the patient’s environment. A bright room with a view of a park, for example, is thought to be more beneficial than a room that faces an air shaft. Likewise, a room with appealing art in it is better than one with blank walls.

There’s no better example of how this has been put into practice than the MD Anderson Cooper Cancer Center in Camden, New Jersey. The state-of-the-art treatment facility was completed in late 2014 and is still filling out its four-story building. Most recently, it installed a breast cancer wing. Visitors to the outpatient facility pass through a light-filled lobby dominated by a monumental decorative work, a color-changing Tree of Life made of translucent acrylic panels.

I had a tour with Susan Bass-Levin, president of the Cooper Foundation. Bass-Levin is a former mayor of Cherry Hill, NJ, a three-time commissioner of the New Jersey Department of Community Affairs and former deputy executive director of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. She is also a cancer survivor and an art lover, which gives her a special passion for this job.

The Cooper Center has more than a hundred works of art. There’s hardly a place you can go where an artwork is not in sight—corridors, waiting areas, examination rooms, nurse stations—even the hallway that patients pass through when arriving or leaving by ambulance. More importantly, the quality is many levels above the typical mass-produced art you often see in hospital corridors or hotels.

The art here has an intimacy and an earnestness about it. You sense the personality and the commitment of the artist. That still leaves a huge variety of art from which to pick in today’s eclectic art scene. Much of the trendiest and most expensive art is inappropriate for healing environments. That includes all the cutting-edge art that plays conceptual games or is confrontational or subversive (think Damien Hirst’s shark in formaldehyde or Jeff Koons’ chrome balloon poodle).

So what kind of art is therapeutic for cancer patients?

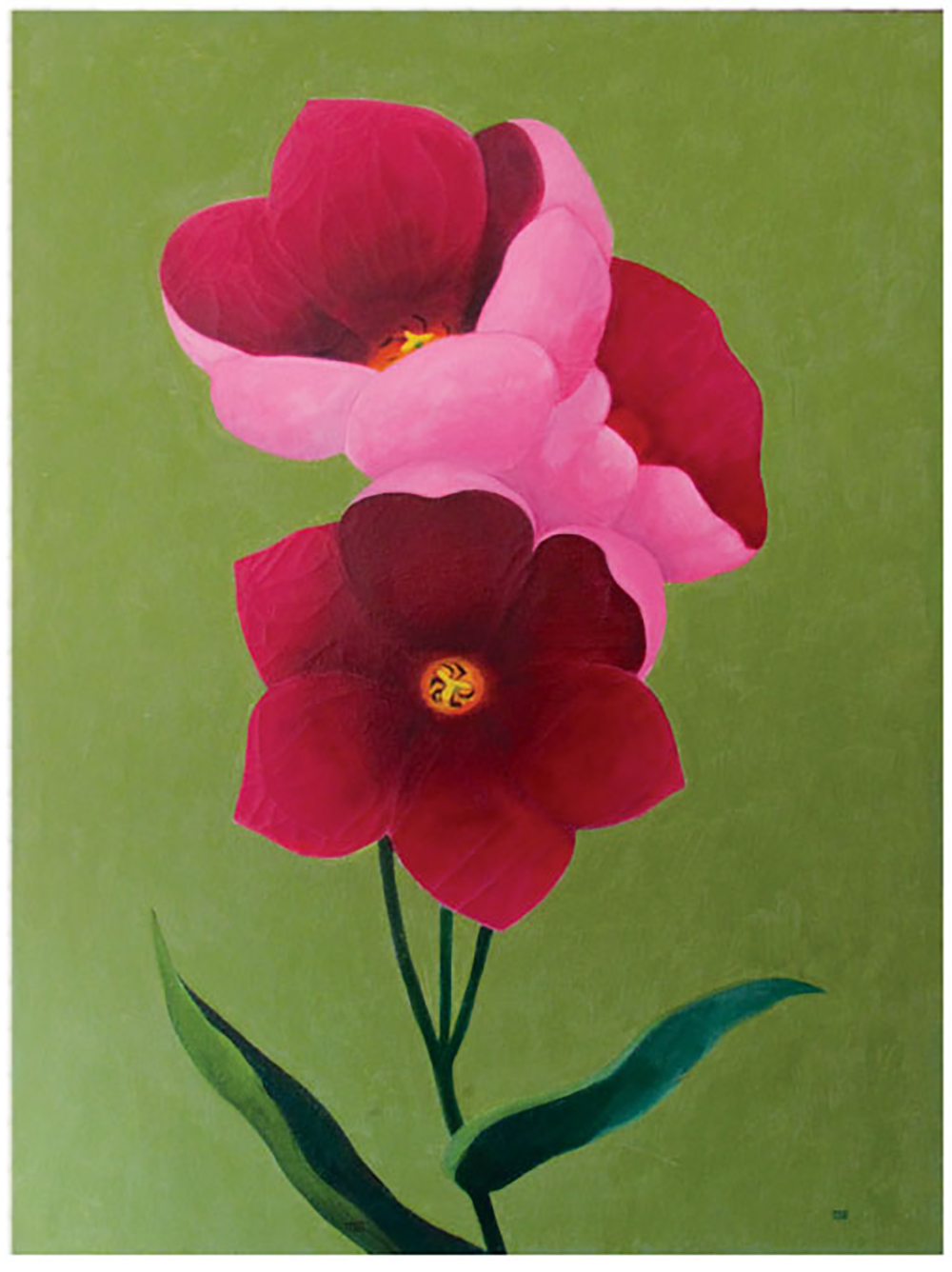

By far the most consistent theme in this art is the natural world. All the photography is of nature. A majority of the paintings are of landscapes or flowers. Even the abstract works tend to have floral or botanical themes. And the mood is upbeat. Old-fashioned beauty may be out of style at the Whitney Biennial or the new Met Breuer, but it’s exactly what is wanted at the Cooper Cancer Center.

“We don’t take art that’s sad and depressing,” Bass-Levin says. “Many of our artists use bright, impressionist palettes.” There are no paintings of dark, stormy scenes. The closest, by Camden artist Jeff Filbert, is of pinkish clouds in a yellow sky over a calm blue ocean. It’s titled Storm Passing, a metaphor, in this setting, for recovery from illness.

One work was rejected because it was all clouds. “It seemed too suggestive of heaven,” Bass-Levin says.

You won’t find portraits here either. In fact, human figures are almost completely absent. The idea is to give viewers a window on a world, to immerse them in a scene without the distraction of other people in it. One exception is a watercolor by Marie Natale of people strolling on the Atlantic City boardwalk.

Natale, like all the other artists and photographers in the collection, is from New Jersey. At first glance, that seems like a mere courtesy or an act of loyalty—a support-your-local-artist kind of thing. But it’s more than that. Using New Jersey artists ensures that many, if not all, of the landscapes will be local also. So the subjects are more likely to be familiar and to resonate with viewers, such as Philip J. Carroll’s painting of a waterway in the Pine Barrens, Diane S. Grimes’ oil of a Long Beach Island marshland, Yuri Lev’s photograph of East Point Lighthouse on the Delaware Bay, and James Toogood’s Cranberry Bog.

Bass-Levin points to the work of Asbury Park artist Laura Petrovich-Cheney’s “message of resilience” for her designs using salvaged wood from Hurricane Sandy.

The art program creates a dialogue of sorts between the artists and the patients. A number of artists have friends or family members who have been patients at Cooper. Some of the artists are themselves cancer survivors and bring that special perspective to their art.

Painter Deb Strong Napple of Somerville is a three-time cancer survivor. In a catalog of the Cooper collection she writes: “When I was undergoing treatment for my cancers, the hardest time was always the waiting—whether for a procedure, a test or for the doctor to deliver the news. Art helped me through the waiting, and I hope it can help others too.”

The new breast cancer treatment wing is named for philanthropist and breast cancer survivor Janet Knowles. The Moorestown resident became a glass-bead artist after her cancer recovery 15 years ago. Some seven years ago, she made a generous donation and committed to the campaign to advance Cooper’s breast-cancer program.

About 104,000 patients are treated at the Cooper Center annually. Most of them are dealing with fear, worry and anxiety as well as pain and discomfort. The upbeat art, Bass-Levin says, creates a soothing atmosphere, one that engenders hope and optimism.

The staff at the Cooper Center are also in this atmosphere. “Taking care of cancer patients can be a very stressful, emotional process,” says Medical Director Generosa Grana, who with Bass-Levin approves every piece. “The doctors, nurses and administrators benefit from this art too.”