Eva Cellini, Late-Life Surrealist

Writer John ZeamanAn artist taps into the unconscious, explores uncertainty.

There’s always been a youthful spirit to surrealism. The embrace of the nonrational, the prankishness, the fascination with the minutiae of one’s own dreams—all bespeak a young sensibility.

What then to make of a 90-year-old surrealist? Not only that, but one who didn’t even take up the style until age 54?

This is the riddle—and wonder—of Eva Cellini, a North Jersey artist who, in her 10th decade, still climbs a steep staircase to her garret studio every day. There she conjures up dark and quirky impossibilities —a monkey in armor, an orchid sprouting from an industrial pipe, a giant lightbulb on a forest floor.

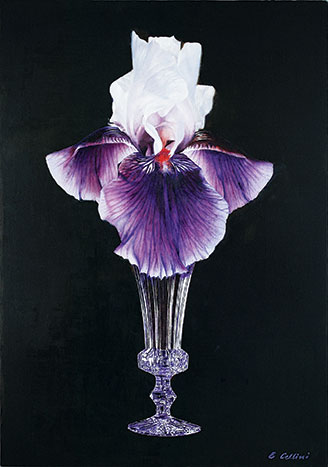

Surrealism has always been radical in content and conservative in rendering. Were its strange subjects not painted so realistically—think Salvadore Dali’s melting clocks or René Magritte’s floating men in bowler hats—its effects would not be so startling. With Cellini, the realism has a particularly elegant pedigree. She paints with the meticulous attention to detail of the old masters. When she paints a crystal goblet, it’s a flawless illusion—the facets and reflections within the glass are all there.

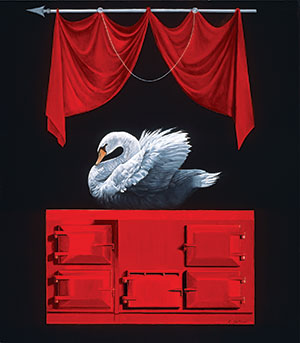

She composes her canvases like stage sets. The backgrounds are almost always dark, often black. She frames her subjects with drapery that function like theatrical curtains. There is a sense of a surprise unveiling, as in a magic act. “Voila!”

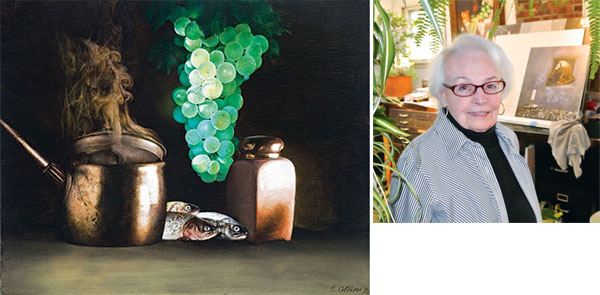

Even in person, Cellini seems to fool the eye. She is small, almost childlike in stature, and looks younger than her years. Her eyes are bright, with a sometimes impish glint. In manners and accent there are traces of her European background. She was born in Czechoslovakia and raised in Hungary. Cellini graduated from the School of Applied Arts in Budapest. Her first job, in 1949, was in a factory that made Communist propaganda banners. She and other artists painted bedsheet-size images of Lenin, Stalin and local party officials for May Day parades.

In 1956, following the failed Hungarian uprising, Cellini and her husband, Joseph, fled across the mountains to Austria. From there, they came as refugees to the United States, sailing into New York Harbor, past the iconic Statue of Liberty on New Year’s Day 1957.

Like others before them, they came practically penniless. But both were talented artists, and before long they were working as commercial illustrators and living in a small apartment on Central Park West. Later, seeking more room, they moved into a house in Leonia, where Cellini lives today.

Transitions

For a long time, Cellini was a graphic artist, working in dry media and watercolor. Interestingly, her move into oils, as well as her first dabble in surrealism, came with a single commercial work. An agent had rejected her because her portfolio was mostly watercolors. She took it as a challenge and set about to learn oil painting. Her husband gave her an idea for a demonstration piece she could submit to the agent. “He knew I liked 17th-century still life, so he suggested I paint a still life in that style then put something modern in it, like a coffee maker,” she recalls. She pitched it to the agent as a sample advertisement that would promote the modern product as “a classic.” It worked.

And she was hooked on oils. That was 36 years ago. In the intervening years, she gradually pulled away from commercial work and settled into the fine art surrealist niche, exhibiting today in galleries in New York City; New Jersey; Aspen, Colorado; and Jackson Hole, Wyoming. Her website is evacellini.com.

The Process

Surrealism, as it originated in the early 1920s, was art’s response to Sigmund Freud’s theories about the unconscious mind. The surrealists peered into this secret cauldron of repressed desires, fears and conflicts and saw a new artistic reality, a “super reality” (surrealite) that would blend the visible and the psychological worlds. To tap into this unconscious material, surrealists used techniques such as automatic drawing, in which the hand was allowed to drift freely across the page without conscious intent.

Cellini’s method, which has some of this flavor, is to randomly sift through images from books and the Internet until something “hits” her, as she puts it. Then she does it again. Her library has a lot of books about science, nature and art, so elements such as flowers, animals and still life figure large.

Then she puts these two motifs together, giving herself free rein with respect to scale and relationship. The method has yielded paintings in which an enormous tiger sprawls atop a pueblo-style house. Or one in which the heads of three giraffes peer into a concrete courtyard at a mysterious flower.

“It’s a very strange process,” she acknowledges. “I often don’t understand what the painting is about until I’ve finished it.” One such painting shows a chimpanzee wearing a suit of armor. The rendering is beautiful, right down to the embossed decoration on the metal suit. She says she was first drawn to the ape’s expression, which seemed unnatural to her. The animal looked constricted in some way, and this was reinforced when she added the armor.

“I made that painting when my husband was very sick. He was bedridden, and I was caring for him. It was very intense. Some part of me felt trapped, straitjacketed, I suppose.” For that reason, she titled the painting Me.

A painting of a swan on top of a red stove is entangled with memories of a difficult time in her past. She was 20 and her house had just been destroyed by wartime bombing. She was taken in by a friend, an older woman who was pregnant and needed help. “She saved my life,” Cellini recalls.

But her status in the house was that of a servant. And for some reason, she recalls, the family members began to berate and pick on her. “It was abusive,” she recalls. “Not physical abuse, but mental abuse.” To preserve her self-esteem, she drew on the old Hans Christian Andersen story of the ugly duckling. “I decided that I was different from them because I was the swan. Only they couldn’t see it.” It was 40 years before this found its way into a painting in which the swan sits atop a stove like the one she worked at.

Meanings & Mysteries

Like dreams, Cellini’s paintings are filled with symbols—keys, flowers, crowns—all of which have meaning, though some remain mysteries, even to her.

“For a while I painted a lot of fish,” she recalls. “I’m not sure what that was about. Fish are often symbols. They can stand for Christianity, but I don’t know what they were for me. Maybe just fish.”

Although psychoanalysis was an underpinning of classic surrealism, Cellini finds parallel inspiration in the principles of uncertainty in modern physics. In quantum theory, physicists concede there are phenomena that resist measurement. “It’s spooky,” Cellini says. “We can only know what’s going on through our own senses. And yet our senses are limited.”

Instead of making the unconscious visible, Cellini wants to remind us that visible reality is not the certainty we think it is. And it’s that twilight zone of uncertainty that she has made both her altar and her playground.

Columnist John Zeaman is a freelance art critic who writes regularly for The Record and Star-Ledger newspapers. His reviews of exhibits in New Jersey have garnered awards from the New Jersey Press Association, the Society of Professional Journalists (New Jersey chapter) and the Manhattan-based Society of Silurians, the nation’s oldest press club. He is the author of Dog Walks Man, (Lyons Press, September 2010) about art, landscape and dog walking.