Beautiful Byobu

Writer Leslie Gilbert Elman

This rare 17th-century two-fold screen shows three Chinese scholars playing fo while sitting in an open boat in winter. It was painted in ink on gold and buff ground by Unkoku Tōeki, a prominent artist born in Hiroshima in 1591. Image courtesy of Gregg Baker Asian Art.

Japanese screens combine art and craft in one exquisite object

At the Winter Show in January, Erik Thomsen Gallery of New York City exhibited a six-panel Japanese folding screen painted with an image of soft white wisteria hanging from bamboo poles and an 18th-century two-panel screen with flowers painted on a background of colorful fans.

London-based antiques dealer Gregg Baker Asian Art brought several Japanese screens to TEFAF Maastricht in the Netherlands in March. One, a muted 17th-century piece, depicts a trio of Chinese scholars in a flat-bottom boat playing go. Another, dating to the 1930s, shows brilliant white egrets amid vivid green willow branches.

This seems like the right moment to talk a bit about these beautiful objects. Measuring more than five feet tall and in the case of the six-panel screen nearly 12 feet across, folding screens such as these originally were used as room dividers and draft stoppers—their name in Japanese, byōbu, means “protection from wind.” Yet their artistry is so refined, it’s clear they were never merely functional pieces; they were intended to be noticed wherever they stood.

Painted in 1934, this pair of two-panel screens are signed and dated by the artist, Ishiyama Taihaku. They depict egrets amid willow branches whose tender green leaves are raised from the surface of the screen. The white painted dots in this spring scene represent cherry blossom petals. The background is silverleaf. Image courtesy of Gregg Baker Asian Art.

Byōbu, which range from two to as many as 10 panels, were used in myriad ways to suit various needs. In keeping with the traditional Japanese architectural style of using sliding partitions rather than fixed interior walls, folding screens were arranged to reconfigure space, making it cozier or more expansive as required. (Single-panel screens, called tsuitate, would have been placed near the entrance to a building, corridor or room.)

Writing about his travels in Japan, a 19th-century English missionary described the screen that separated his sleeping chamber from that of another traveler. It had “quite a landscape painted on it. There is Fusiyama, their sacred mountain, beside curious birds and other things.”

Another 19th-century English visitor to Japan wrote: “A man can remove the entire front of his room, as it is not a brick wall, but a screen of paper, decorated with the favourite devices of storks, cranes, dolphins, and tortoises.”

A pair of two-panel screens might have been used to set off an intimate space for a tea ceremony while eight- or tenfold screens could serve as the backdrop for a special event such as a musical or dance performance.

Typically, folding screens were made in pairs and decorated with complementary or continuous designs, such as seasonal flowers or landscapes, domestic scenes, or depictions from historical events and literature such as the Japanese classic The Tale of Genji. Early pieces, influenced by Chinese art, were monochromatic. As fashion evolved, byōbu were painted in ink and embellished with gold, silver and mineral pigments such as gofun, a white pigment made from ground clam and oyster shells.

Sometimes calligraphy was added after the painting was complete, requiring a steady, confident hand to avoid spoiling the artwork. Some pieces were signed by the artist or stamped with the insignia of a workshop. Most remain anonymous.

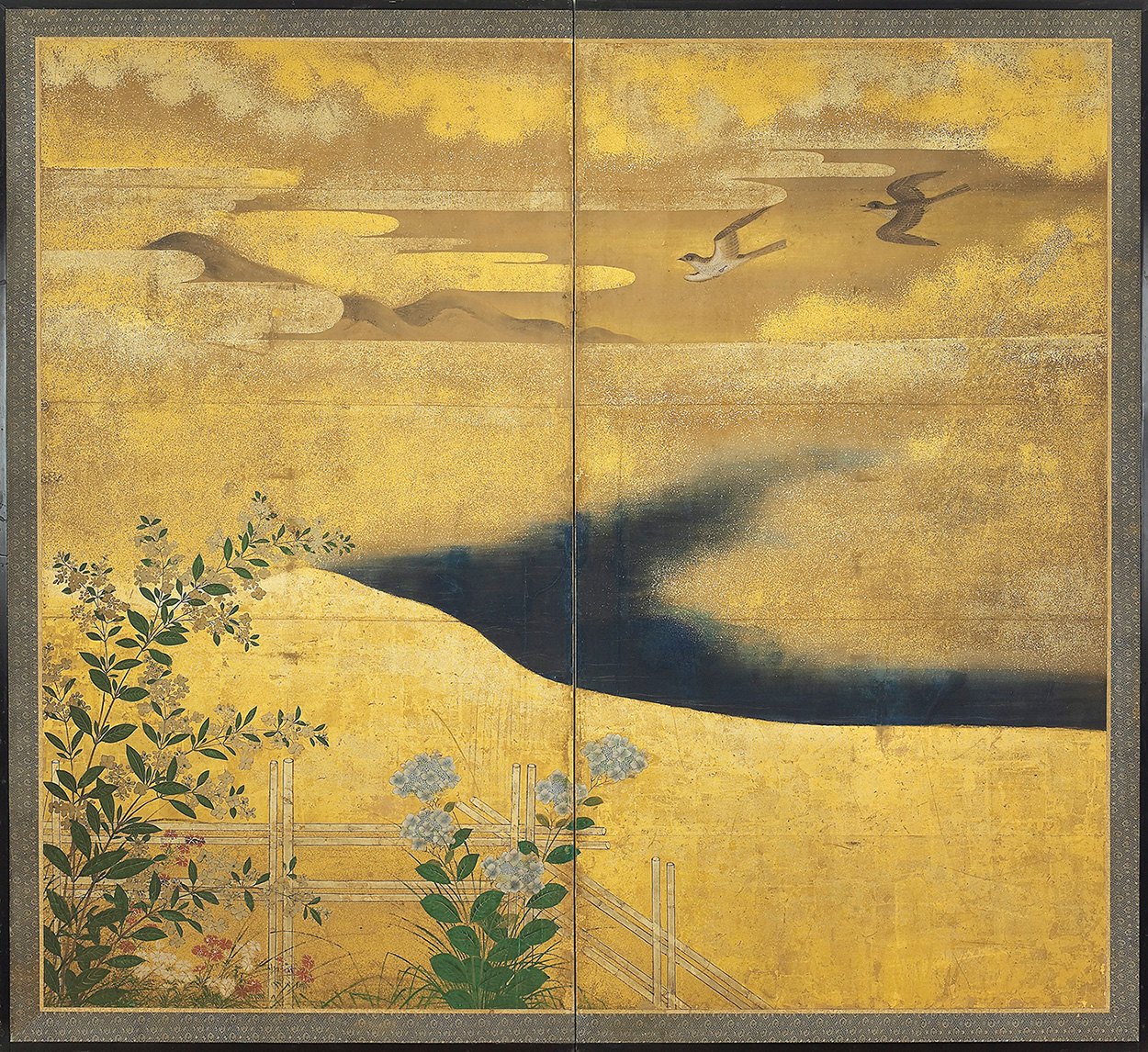

Two nightingales take flight into the clouds over the mountains in this two-panel screen. In the foreground, flowers grow beside a bamboo fence. Measuring about 5 feet 7 inches high and 6 feet a cross, this 18th-century screen is painted in ink and mineral pigment on a gold background. Image courtesy of Gregg Baker Asian Art.

Light and versatile, their simple construction is unique and ingenious.

First, a wood latticework was constructed. It was then covered with layers of paper built up to make the panel surface in a process called karibari, which helps the panel survive changes in temperature and humidity. Panels were connected to each other with washi paper hinges—flexible, secure and surprisingly durable. This hinge system eliminated the need for frames between the panels, creating an uninterrupted surface on which to paint the scene. The screens were made to stand with the hinges bent. (Even though collectors normally display them fully open and hung like a painting, over time this will weaken the paper hinges.)

Byōbu are fragile, as you’d expect any object made from centuries-old paper to be. Yet a remarkable number have survived intact through centuries. That’s partly because, despite their functionality, they always were treated as works of art, especially by European traders who brought Japanese screens back home with them from Asia. Today’s collectors consider them as precious as fine art and can expect to pay from tens of thousands of dollars for a single screen up to more than a million for an exceptional piece by a known artist. And like fine art, byōbu are a never-ending source of pleasure to the eye.

Leslie Gilbert Elman is the author of Weird But True: 200 Astounding, Outrageous and Totally Off the Wall Facts. She writes about antiques and other subjects for Design NJ.