Art (With an Explanation)

Writer John Zeaman | Location Newark, NJA visit to the Paul Robeson Galleries at Rutgers Newark.

In an art world that can often seem hermetically sealed off from the rest of society, the Paul Robeson Galleries at Rutgers University in Newark, New Jersey are the opposite. They want to be as engaged and as relevant as possible—while still being cutting edge, of course.

The galleries do this by putting on shows that have intriguing themes and subjects. Consider the titles of some exhibits from the flagship gallery: “The (Not So) Secret Life of Plants,” “Lift-Off: Earthlings and the Great Beyond,” “Hair” and “Datascapes.”

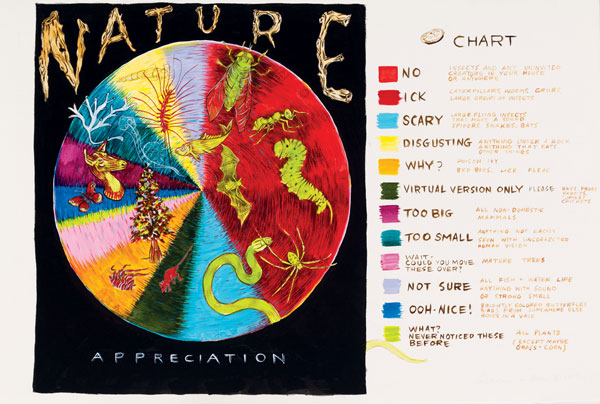

A recent show titled “The Undesirables” was about peoples’ uneasy relationship with creatures typically regarded as pests: rodents, bed bugs, creepy crawly things, disease microbes and the unfortunate birds that slam into windows. The works on view included classically composed still lifes with road kill, two desiccated rats dressed in Mickey and Minnie Mouse outfits and—hold onto your hat—an abstract painting done in paint mixed with crushed up cockroaches.

Reaching for a Broad Audience

If it sounds a bit sensational, well, it’s all calculated to lure non-art lovers into the galleries.

“If we did a show on categories like realism or abstraction, people who weren’t already interested in art might not respond,” gallery manager Caren King Choi says. “But if it’s a show about spiders, they may come in to have a look. Then we’ve started a conversation.”

She and director and chief curator Anonda Bell are good at getting these conversations going. They are also very adept at getting the art out into public spaces where people can’t avoid it.

There are no fewer than eight “galleries” in the Paul Robeson Campus Center. Some may be only lounges, hallways and stretches of wall, but they’re not just there for overflow from the main gallery. Each one is doing a separate show. Add to that the Criminal Justice Gallery in the law school building and a program of one-year “pop-up galleries” that are doing exhibits on a rotating basis in five campus buildings and you’ve got 10 shows going on simultaneously.

Are they planning to take over the campus?

“We joke about that,” Choi says. “But we’re kind of serious about it too.”

The attempt to appeal to the broadest possible audience dates back to the Robeson Galleries’ early days in the late 1970s and early ’80s, Choi says. At the time, memories of the city’s 1967 race riots made the surrounding suburban population leery of visiting Newark, she says. The Robeson Galleries had to try harder than other art venues to draw people in. As they’ve grown in stature and popularity, they’ve begun to exhibit artists not only from New Jersey, but also from New York City and beyond.

The Robeson Galleries’ penchant for quirky themes and connections shows even in the tricky names they’ve given to the different galleries. A space next to the campus center’s Starbucks is called the Pequod Deck because Starbuck was a minor character in “Moby Dick” and the Pequod was the name of the whaling ship. An astronomical theme unites the remaining galleries, presumably because they are “satellites” of the main one: the Messier Gallery, named for an 18th century French astronomer, two “Orbit” galleries and one called “Nova.”

Branching Out

The seeming ease with which the Robeson Galleries can build a show around any given theme is made possible by a postmodern genre of art in which artists—like writers or critics—analyze or deconstruct some subject. It began with the identity-based art of the 1980s and ’90s in which the buzzwords were “race, gender and identity.” Nowadays, artists have branched out into environmental issues, animal rights, globalization, media saturation, capitalism, dystopian fears or science run amok.

Or just plain dirt.

Here is a description of the 2015 “Empire of Dirt” exhibit: “Dirt is a substance so common that it is known to all. It may be dust, soil, earth, clay, loam, grime, silt, filth, or mud. It is waste, excrement, rubbish, and bacteria. It is reviled and cherished, an enemy in the home or laboratory and a foundation for plant life and mighty buildings.”

It’s not the sort of thing that would have inspired Vincent Van Gogh or Claude Monet, but it’s apparently catnip for today’s sociologically inclined artists.

Making Statements

The most overtly political art is over at the law school. Recently, the Criminal Justice Gallery exhibited the work of Newark artists Jerry Gant and Bryant Lebron, who reflect on the highly publicized cases of black men killed by white police officers. Lebron presents a repetitive series of storyboard images in which a character confronting a new case thinks, “That could’ve been me…”

“The Death Penalty Ladies Society” was a 2013 exhibit in which artist Janice McDonnell spoke to the issue of capital punishment with a series of portraits in which 12 executed women were portrayed as genteel socialites like those depicted in the portraits of John Singer Sargent.

Artists who want to spread out, but don’t mind having their murals painted over at the end of the show, can have their way with the walls of the Messier Gallery. Newark artist Armisey Smith’s ambitious One Worm at a Time (on view until July 28) is a baroque, surreal work in which plant forms and human anatomy merge, swirl across walls and creep around corners. The piece, which manages to be both lurid and meditative at the same time, reflects the artist’s struggle with a biologically based depression.

The energy feels boundless at the Robeson Galleries. How what is essentially a two-person operation can mount so many shows, put out catalogs, and organize talks and outreach programs is anybody’s guess. True, the art can seem a bit too literary—a bit too much like literary theory, actually—in which all the artists’ statements use the same academic jargon. But the Robeson Galleries are part of an academic institution, after all, a place where theory and analysis are very much at home.

Let the conversations begin.

Columnist John Zeaman is a freelance art critic who writes regularly for The Record and Star-Ledger newspapers. His reviews of exhibits in New Jersey have garnered awards from the New Jersey Press Association, the Society of Professional Journalists (New Jersey chapter) and the Manhattan-based Society of Silurians, the nation’s oldest press club. He is the author of Dog Walks Man, (Lyons Press, September 2010) about art, landscape and dog walking.