Make Mine a Toddy

Writer Leslie Gilbert ElmanThe founding fathers’ favorite drink inspired some unusual objects.

As winter rolls in, you might contemplate sipping a hot beverage to keep the chill at bay. Maybe a toddy, smooth and sweet with a spirited kick to warm your bones. If such thoughts occurred to you, you’d have something in common with America’s founding fathers. They were known to enjoy a toddy or two at home or in a tavern. (Except the great Philadelphia physician Benjamin Rush, who vehemently condemned toddies and other “ardent spirits.”)

A party of 13 patriotic Freemasons gathered at Daniel Smith’s City Tavern in Philadelphia in 1775 and reportedly demonstrated their commitment to independence for the 13 colonies by eating 13 dishes of beef and consuming 13 bowls of toddy. Two years later, in 1777, frugal New Englander John Adams wrote to his wife, Abigail, complaining about the high cost of toddies in Philadelphia. George Washington and Thomas Jefferson regularly ordered bowls of toddy at Mrs. Campbell’s, a favorite spot in Williamsburg, Virginia. And local lore in Amherst, Virginia, says that in 1788, two politicians celebrated their election by buying 98 gallons of toddy for their constituents.

In Imbibe!, his excellent book of cocktail history, David Wondrich, calls the toddy “a simple drink in the same way a tripod is a simple device: Remove one leg and it cannot stand, set it up properly and it will hold the whole weight of the world.” The “legs” of a toddy are hot water, sugar and spirits—“rum (or whiskey if you were out on the frontier, brandy if you were posh, applejack if you were from New Jersey, gin if you were of African or Dutch extraction, and so on.)” Grated nutmeg on top was common, but not mandatory. The important thing was the warmth and sense of well-being the drink provided.

Mixing it Up

Made by the quart, toddies were intended to be shared; a sign of conviviality in a tavern and hospitality at home. Ingredients were combined in an attractive vessel, stirred until the sugar melted and then poured out using various accoutrements devised especially for the task.

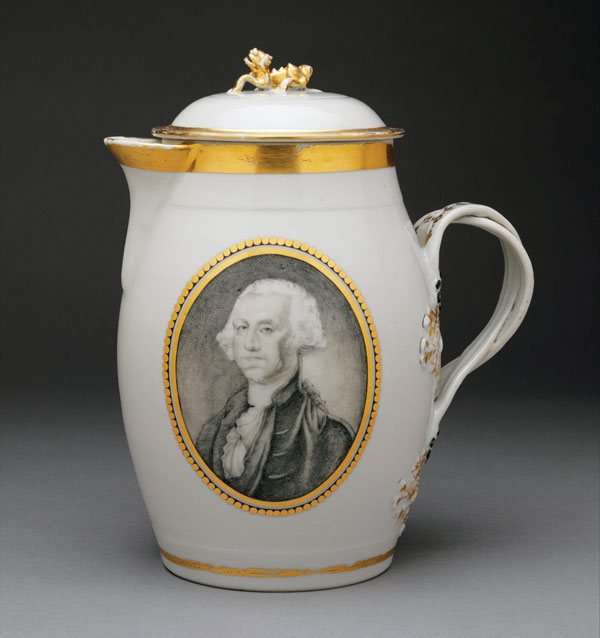

Toddy jugs held enough for a small group, the lid kept the liquid warm and the spout made it convenient to pour the toddy into the heavy, footed glasses in which it usually was served.

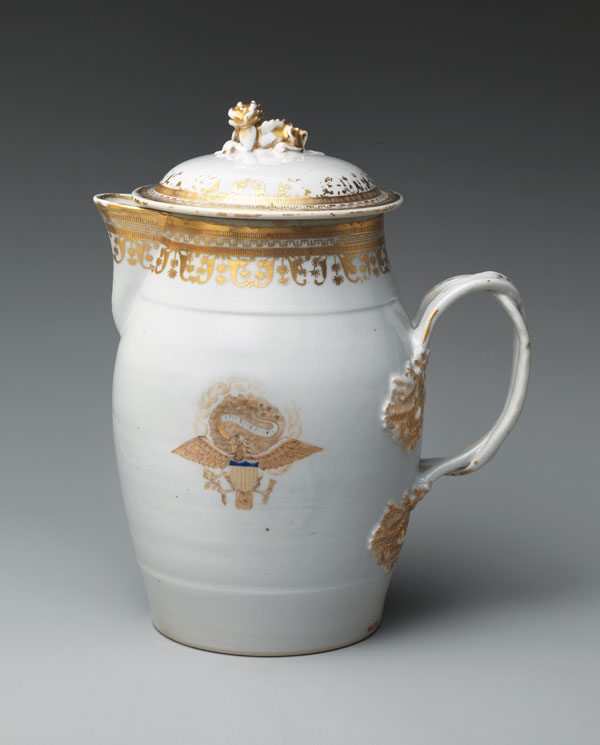

Several of the toddy jugs now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City were made in China around 1800 specifically for export to the United States. Smooth, white Chinese porcelain had been highly desired in Europe ever since Marco Polo started writing home about it in the 13th century. Even after the scientists at the Meissen porcelain manufactory in Germany devised a formula for making their own white hard-paste porcelain in the early 1700s, Europeans still clamored for porcelain from the Far East.

Not surprisingly, the fashion in Europe was also the fashion in the United States. Yet unlike their Old World counterparts, colonials liked their decorative arts with a little American patriotic flair. So Chinese porcelain manufacturers obliged them, decorating objects with American eagles, stars and stripes, oak-leaf clusters and the like. It’s easy to assume these pieces were made in the U.S.A. until you take a close look at the lids. Those little gilded Lion of Fo finials make them unmistakably Chinese.

Lifting the Spirits

Larger toddy mixtures were prepared in punch bowls. The mixture was stirred with a specially designed spoon that had a flattened end to crush the loaf sugar and help it dissolve. Then it was poured into individual glasses using a long, slender toddy ladle or a device called a toddy lifter.

Even among unusual objects made for singular purposes, the toddy lifter is an odd little invention. It resembles a decanter with a bulbous base, a flat collar around its open neck and, most importantly, a hole in its bottom. Used like a siphon, the bulb of the toddy lifter would be submerged in the toddy bowl until it filled with liquid. Placing a finger over the open neck created a vacuum to hold the liquid inside the bulb. When the toddy lifter was positioned over a glass, the server lifted his finger and the drink poured out.

Why someone decided this was a good way to serve beverages is anyone’s guess, but it would have been entertaining to watch—a bit of a crowd-pleaser, like the toddy itself.

Leslie Gilbert Elman is the author of Weird But True: 200 Astounding, Outrageous and Totally Off the Wall Facts. She writes about antiques and other subjects for Design NJ.