Circus Sideshow

Writer John ZeamanThe Art of Amazement.

By the time you read this, Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus will be no more. The owners announced earlier this year that in May, after 146 years, “The Greatest Show on Earth” would fold up its tents. Likewise for Lincoln Center’s charming Big Apple Circus, which has declared bankruptcy. The world’s only thriving circus, the Montreal-based Cirque du Soleil, has redefined the circus as something more like a big Broadway show.

It feels as though an important part of Americana has disappeared. Circuses promised unique spectacles: A stream of clowns pouring out of a tiny car. Tightrope walkers forming human pyramids. Dogs running up ladders. Elephants in a conga line.

The old circuses also had smaller, sometimes seedier entertainments that were not under the “Big Top.” These, also nearly extinct, were the sideshows.

This spring, the Metropolitan Museum did an exhibit on a painting by the pointillist Georges Seurat titled Parade de Cirque, or Circus Sideshow (shown on page 57). Painted in 1888, it depicted a line of circus entertainers on a narrow stage and the people who have gathered to watch. The musicians are a teaser, a free sample meant to entice people into the tent behind them.

The painting is unusual for the artist, who typically used his system of colored dots to maximize effects of light. Here, he has conjured up a nocturnal scene of shadows and silhouettes illuminated by nine flickering gaslights.

Seurat’s subject was a real place. Old photos identify it as the popular Corvi Circus, which regularly visited Paris in those days. But the treatment is far from realistic. Everything is simplified, reduced to its geometric essence. What should have been a noisy scene feels somehow quiet, as if a solemn ritual were taking place. The most prominent musician is a slim, almost feminine figure wearing a cone-shaped headdress. He looks more like a snake charmer than someone playing a slide trombone.

It’s an evocative, mysterious picture. Nobody at the time quite knew what to make of it. To this day, it remains an anomaly in the short-lived artist’s body of work.

The historical surprise of this exhibit was that Seurat was far from alone in depicting such scenes. The sideshow, which dated back to the Middle Ages in France, was a subject that seemed irresistible to generations of French artists. In the 1860s, the great caricaturist and satirical artist Honoré Daumier reveled in the raucous and coarse character of the sideshow. The young Pablo Picasso followed a popular convention in portraying the saltimbanques—acrobats and other sideshow performers—as sad and alienated characters. The most stunning of these portrayals is Fernand Pelez’s epic Grimaces and Misery—The Saltimbanques (shown on pages 56-57) a 20-foot-wide canvas with a line of life-size figures, from weary little girls in ill-fitting tights to bored and burned out musicians with drooping heads.

The circus sideshow also attracted French caricaturists and political cartoonists who found the motif perfect for depicting politicians as hucksters or leading figures of the day as clowns or buffoons.

In America, sideshows graduated from enticements to independent entertainments. As part of carnivals and amusement parks, they offered up bizarre, believe-it-or-not acts. Performers did seemingly impossible things, like swallowing swords, breathing fire or driving nails into their heads. Even more popular were the so-called freaks, the midgets, giants, bearded ladies, Siamese twins and those with missing or additional limbs.

The most famous sideshows were in New York City’s Coney Island, that turn-of-the-century playland by the sea with its legendary amusement parks: Dreamland, Luna and Steeplechase. One popular sideshow-type attraction was Lilliputia, a miniature city inhabited by dwarves and midgets.

By midcentury, Coney Island was in decline, its honky-tonk entertainments eclipsed by the wholesome Disneyland aesthetic. It was judged unseemly to gawk at people with physical abnormalities (although Diane Arbus became famous for photographing them). Sideshows closed and were replaced by more profitable mechanical rides.

In the 1980s, nostalgia for Coney Island’s glorious past led to the creation of Coney Island USA. Led by Dick Zigun, the unofficial “mayor” of Coney Island, the group launched the annual Mermaid Parade, Burlesque at the Beach, the Coney Island Tattoo and Motorcycle Festival, the Coney Island Museum and, of course, the Coney Island Circus Sideshow.

The resurrected sideshow didn’t bring back the likes of “Lobster Boy” or “The Four-Legged Girl.” Performers do traditional sideshow acts, such as fire-eating, escape artistry, snake dancing, electrical conduction and the juggling of knives and other dangerous objects.

Enter Marie Roberts, professor of art at Fairleigh Dickinson University in Teaneck. Roberts has roots in Coney Island. Her uncle, Lester Roberts, was a barker for Dreamland Circus Sideshow in the 1920s. Uncle Lester, Roberts says, brought the freaks and performers to the family home in Gravesend. They were his friends.

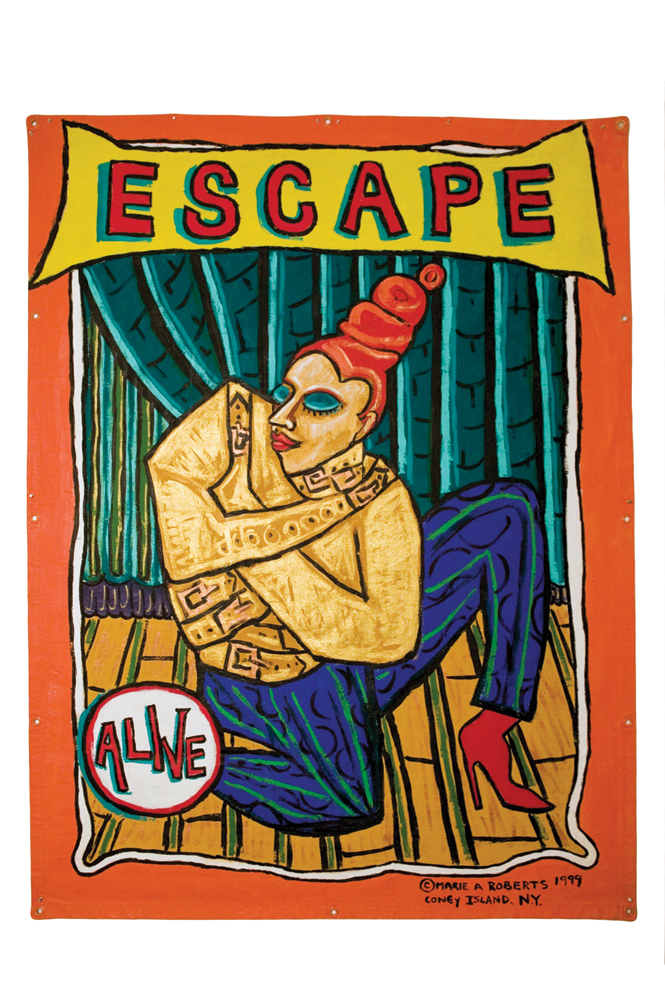

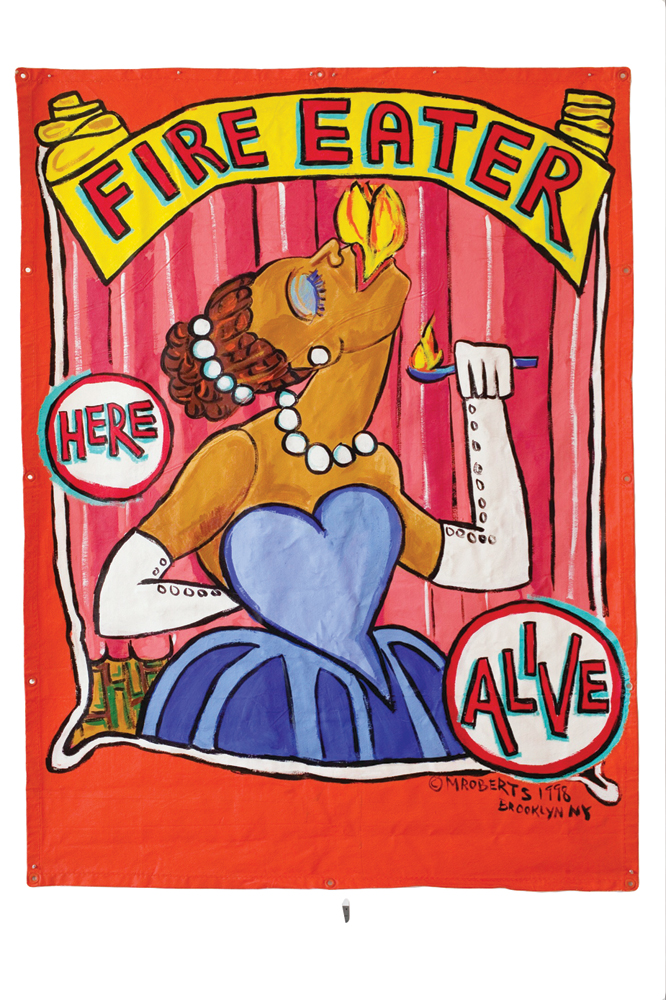

In her earlier career, Roberts was an easel painter who sometimes did Coney Island subjects. But in 1997, Zigun asked her to create some banners for the rejuvenated sideshow. Banners are a tradition as old as sideshows themselves. You can even see them in Seurat’s painting, though he blurred out the details. Roberts enlisted a bunch of students and together they knocked out 25 banners.

In the process, Roberts had an epiphany. “Suddenly my family background and my art training came together,” she says. She had always wanted to do art for the masses. She never forgot a trip to Italy where she saw the way great art is integrated into public spaces.

Twenty years later, Roberts is Coney Island USA’s artist in residence with a studio on the second floor of the Coney Island Museum.

Roberts is aware that not everyone understands this kind of art. “There’s a lot of prejudice because people think—‘Ewww! Gross! Why do that?’ They’re put off by sideshow subjects. I wasn’t brought up that way. To me, it was everyday life.”

Her banner paintings of fire-eaters, contortionists, snake dancers and the like—traditionally edged in orange and rendered in a bold, cartoonish style—are prominently displayed outside the sideshow on Surf Avenue. Some have been transferred to shirts and tote bags, sold in the Coney Island Museum gift shop.

The Seurat show was an extra validation for Roberts. Here were some of history’s greatest artists engaging with her subject.

She believes the appeal of the sideshow is the promise of childlike wonder. “It seems like in the modern world we’re searching for amazement, but there is so little that is truly amazing. The thing about the sideshow and the banners is that people are doing real things you don’t think are possible.”

Seurat’s Circus Sideshow hints at that amazement, even though you can’t make out the blurry banners and the performers are mere musicians. His abstraction of the ordinary gives the scene a timeless feeling, and the strange sinuous trombonist hints at something otherworldly.

It’s all about anticipation. What awaits you inside? Should you enter?

Seurat did another painting of a circus interior. It’s a wonderful image in which a female acrobat balances impossibly on a galloping white horse. It’s amazing, but it’s a secret revealed. It doesn’t have the mystery of Circus Sideshow, that dreamy prelude, like the night before Christmas, when magic seems possible.

Columnist John Zeaman is a freelance art critic who writes regularly for The Record and Star Ledger newspapers. His reviews of exhibits in New Jersey have garnered awards from the New Jersey Press Association, the Society of Professional Journalists (New Jersey chapter) and the Manhattan-based Society of Silurians, the nation’s oldest press club. He is the author of Dog Walks Man (Lyons Press, September 2010) about art, landscape and dog walking.